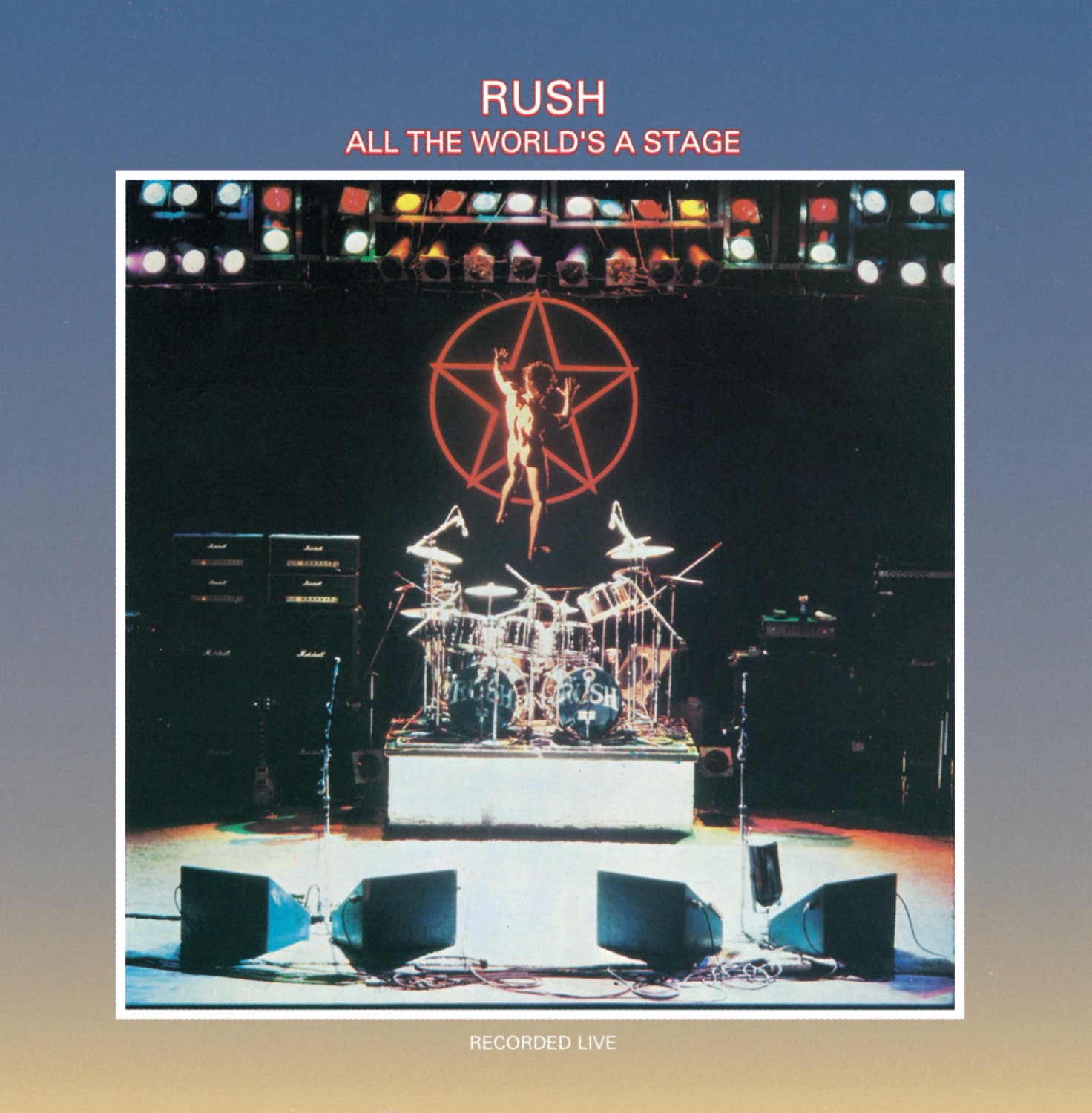

For all Rush’s reputation as dazzling progressive rockers on their studio albums, they have an enviable parallell reputation as a thunderously hard rocking live act. While their 70s studio albums are heavy on meticulously played brainiac sci-fi / fantasy concepts, their first live offering, All the World’s a Stage, confirmed that when it came to live performance, they coupled their superlative studio sound to energetic power trio dynamics.

I have to confess, I’ve taken a long road to becoming a Rush fan. For years they were a band I could admire the musicianship of, but I struggled to understand their fan’s devotion towards them. Then suddenly, hearing this album, I got them and the rest of their albums started to reveal their appeal to me. I understood what it was that made Rush the great rock band that they so undoubtedly are.

While live double albums were plentiful during the seventies, few manage to capture the essence of the band in question as well as All the World’s a Stage, especially when you consider that only one of the band’s four studio albums to that point had been even a medium-size success. This is the sound of Rush celebrating the fact that sticking to their guns when their record label wanted them to sound like Bad Company had paid off and they were doing things on their own terms.

When it comes to Rush, much of their appeal is that each band member was an absolute master of their craft. Where in the studio Alex Lifeson’s guitar work can sound flash, but ultimately restrained, on All the World’s a Stage he’s given room to unleash the rock beast within. From the life-affirming riffing that opens “Bastille Day”, to his liquid playing through the first section of “Something for Nothing” and displaying his diversity throughout “2112”, the whole album works as a showcase for Lifeson, and proof if any were needed, of exactly why his guitar playing has always been held in such high esteem.

Talking of high, vocalist and bass player Geddy Lee, also shows his range on All the World’s a Stage. Geddy’s ability to hit the high notes is striking throughout the album, even though his vocal debt to Robert Plant in Rush’s early career is particularly obvious on “In the End”. On the live stage, Geddy’s bass-work reaches a new level, thundering beneath Lifeson’s lithe guitar work and his playing impresses throughout the album.

Of course, no review of any Rush release is complete without mention of Neil Peart’s drumming. While he rose to prominence during a period when there were plenty of great rock drummers about, Peart has always stood apart as a drummer of technically staggering technique and on All the World’s a Stage, he cements his reputation as a player of astonishing ability.

This being a 70s live album there’s soloing aplenty, with both Lifeson and Peart getting lengthy moments in the spotlight, but this doesn’t mean the album drags, instead it clips along at a pace throughout. Perhaps the most impressive thing about All the World’s a Stage is the blistering musical interplay of all three band members and the fact that such a gloriously huge sound can be produced by just a trio of musicians. There’s a danger that such impressive musicianship could come across as aloof and sterile, however Rush manage to harness their raw power in a way that it connects on a very primal level, as they streamline some of their lengthier numbers. The effect of all this is the fact that the likes of “2112” and “Bytor and the Snowdog” start lodging in your brain like never before – seriously since I’ve been refamiliarising myself with All the World’s a Stage for this review, “The Temples of Syrinx” has managed to take up permanent residence in my psyche. Trust me, it’s heady stuff.

This plush heavyweight vinyl reissue is destined to become a much sought after release by the band’s fans and serves as a reminder that for all their technical dexterity, on stage Rush are a rock band of thrilling power. If you’re a rock fan who has yet to discover the joy of Rush, this could be the album that convinces you. It certainly did me.

No Comment