The rise of punk triggered a wide variety of reactions among more established acts. Led Zeppelin nodded in approval, and continued to be Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd channelled their own disenfranchised feelings into the bleak Animals. A few other acts underwent underwent various identity crises, with some attempting to go ‘pop’ with mixed success (Emerson, Lake and Palmer failed with the awful Love Beach before calling it a day, while Genesis went on to be dizzyingly successful), while Black Sabbath struggled with their own problems, and The Rolling Stones dabbled with disco. Perhaps the most radical reaction though was that by Jethro Tull. Having already signalled that they were already anticipating being overwhelmed by the next big youth movement on 1976’s oddly under-appreciated, Too Old to Rock and Roll; Too Young to Die, in February 1977, Ian Anderson and his bandmates released Songs From the Wood, which was basically the sound of Jethro Tull that the new popular culture that would make them look utterly irrelevant was inexorably rising, and yet somehow they still came to the conclusion that it was the ideal time to go morris dancing.

Okay, so maybe it’s not quite as bad as all that, and in retrospect it was the bravest move that any of the rock establishment made in reaction to the upsurge of punk. By increasing the long-present folk rock elements in their music, Jethro Tull set themselves swimming against the youth culture current, and even non fans had to ponder the audacity of their decision. Thing is, it worked. Sort of. Jethro Tull continued to thrive on their own terms, and Songs From the Wood would prove to be the first of a trilogy of folk rock albums which saw them gain a second wave of fans who were happy to embrace the ‘Hey Nonny Nonny’ness of it all.

In that sense, Songs From the Wood was a brave, career saving, move for Jethro Tull. Long time fans thrilled at the sound of Tull bolting their hard rock riffs and progressive tendencies to folk rock, and songwise, Ian Anderson seemed to be a writer reborn. Songs like the sweaty-riffed “Hunting Girl” and the glorious title track are career highlights, and on “The Whistler” Anderson demonstrated that he could make the re-tooled Tull sound quite commercial too. It’s also home to Tull’s last bonafide hit single too, with the seasonal “Ring Out Solstice Bells”.

As well received and loved as Songs From the Wood is, there’s also a negative side to it that doesn’t always get talked about. While “Ring Out Solstice Bells” was the band’s last hit, it’s also one of the few bits of Top of the Pops footage of Tull that gets trotted out in retrospectives of the 70s, along with a frankly cringe worthy performance of “The Witches Promise”, neither of which have done much to combat the tired opinion of the tastemakers that Tull were anything more than wild-haired twee folk-rockers. Actually, one of the main things that holds Songs From the Wood back from being a truly great album is that it suffers from being just a bit more twee than is strictly necessary. Songs like “Velvet Green” and the epic “Pibroch” make Tull sound like a pale shadow of their former selves, which given that “Pibroch” features some distinctly heavy metal guitar wailing from Martin Barre, is a real shame.

That said, musically, Tull were at a peak in the late 70s. The wonderfully fluid bass work of John Glascock had kicked the rest of Tull up a gear in terms of musical performance, and his rhythmic partnership with drummer Barriemore Barlow was the finest that Tull ever had in their long career. Of course, Ian Anderson remained one of the more unique and compelling frontmen of his generation, and Martin Barre was always one of rock’s most versatile guitar players, and combined with the addition of long time collaborator and orchestral arranger David Palmer as a full time member of the band on keyboard and organ, alongside long-standing piano and organ player, John Evans, it all resulted in Jethro Tull had a much more full and rounded sound than they had previously, and as such Songs From the Wood is one of their lushest sounding albums.

While Songs From the Wood may fall short of greatness due to a tendency to lean a little too heavily on twee folksiness here and there, no one could argue that it isn’t one of Jethro Tull’s key albums, simply because of when it happened. By going against the grain of popular culture at the time, they may not have dodged the bullet of punk, but they were no more than grazed by it, and they probably would not have survived without embracing folk sounds a little more closely than they had previously. It was a brave move that could have destroyed their career if it hadn’t been done well, as it was, Anderson and his bandmates were one of the few acts of the era with enough talent for them to pull it off without it making them look utterly foolish.

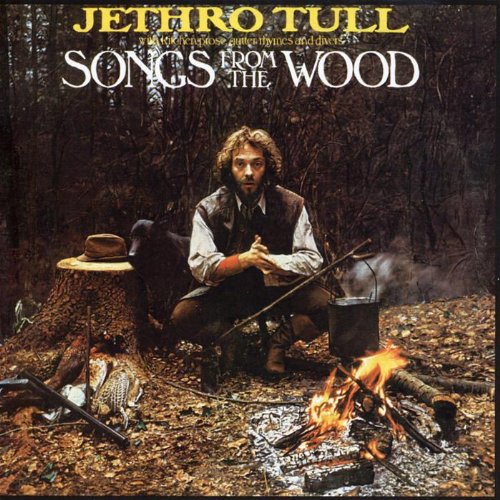

Classic Album: Jethro Tull – Songs From the Wood

No Comment