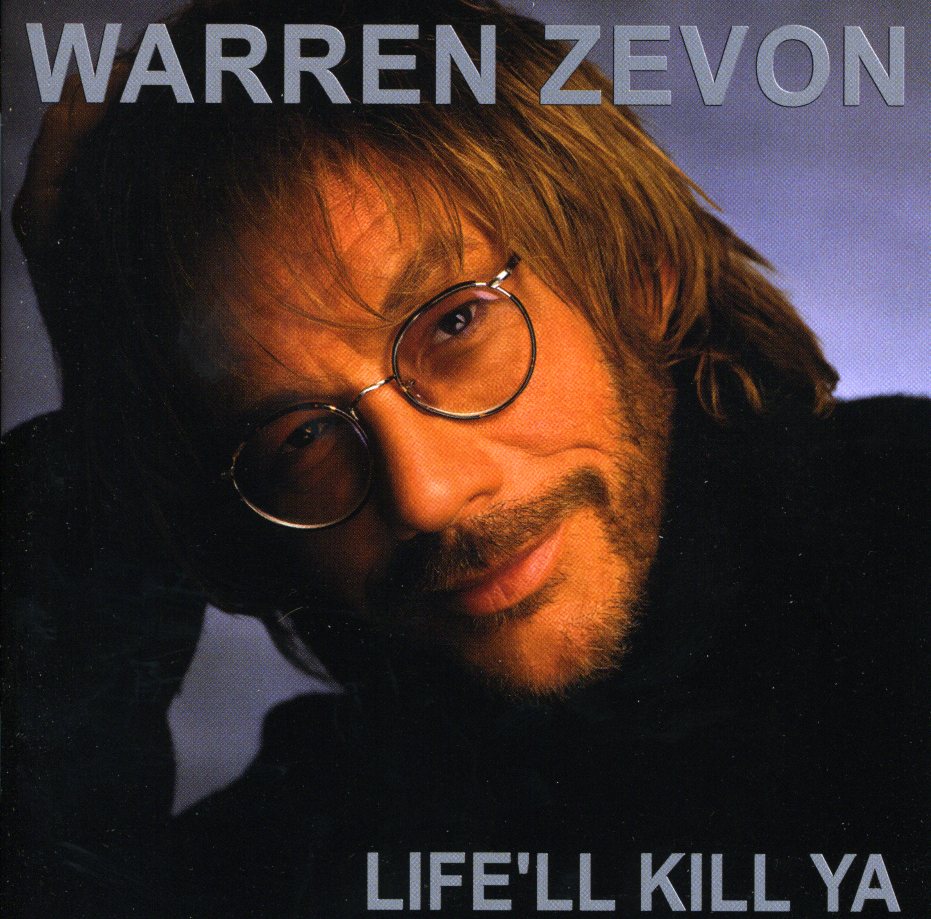

It’s tempting to retrospectively view Warren Zevon’s final three albums as a loose trilogy based around the theme of mortality. While the post cancer-diagnosis musings of My Ride’s Here and the acceptance of The Wind can certainly be seen as being directly influenced by the fact that Zevon knew that he was reaching the end of his life, Life’ll Kill Ya was released before he knew his card was marked. Perhaps it was a case of Zevon tempting fate, but the themes explored here would become eerily apt over the last few years of his life.

After being notable only for his absence through the late 90s (Mutineer registered barely a blip on even the smallest commercial scale and the compilation I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (An Anthology) did nothing to raise his profile), Life’ll Kill Ya was somewhat of an unexpected return to bleak comic form for Zevon. While his commercial fortunes were little better than they had been a decade previously, he had seemingly hit upon a rich seem of inspiration which ensured that this would be his strongest release since perhaps his late 70s peak. This was the release where Zevon seemingly decided that he had tired of being a difficult to handle outsider and had instead realised that he’d be much happier as a wry and knowing elder-statesman singer-songwriter. This modest shift of self-perception in place Zevon finally seemed happy with not only how he saw himself, but how he wanted the world in general to view him, even though his fans had long spoken of him in the same hushed tones of reverence as Dylan, Springsteen, Newman and Young, four names that had endured mixed fortunes since their 70s peaks themselves.

Life’ll Kill Ya opens with the only song from the album I was familiar with prior to me purchasing it. “I Was in the House When the House Burned Down” finds Zevon in stripped-down mode, harmonica wailing and guitar clattering. While I can’t claim it’s one his best songs, it’s certainly a fine tune and arguably the albums most accessible moment for the uninitiated. It also sets the somewhat spartan tone of the album, which works surprisingly well and has resulted in an album which hasn’t aged as badly as so many released about this time. It also has its lighter moments too, with Zevon’s morbid humour rattling about on often-forgotten tunes like “For My Next Trick I’ll Need a Volunteer”. Again, it’s musical strength lays in the fact that it is not overdone or over-thought out, the song arrives, entertains, and then bggers off before you get bored of it.

The beating heart of this album are the three tunes it is best remembered for, a trilogy of illness and death fixated songs. The title track lollops along nicely and would have fitted on any of Zevon’s big(ish) sellers from the 70s, “My Shit’s Fucked Up” is one of Zevon’s most morbid and prophetic tunes, with the profanity used ensuring that it gets no mention on the tracklisting on the back of the album. Most moving though is the closing “Don’t Let us Get Sick”, a plea for eternal youth from a man whose youth is long behind him and only had failing health and diminishing faculties in front of him. Anyone of these three would have made a fitting self-penned audio-eulogy for Zevon and (the circumstances of my eventual passing taken into account) are going to be high on my own personal wishlist too.

No Comment