FOR FAR too many music fans here in the UK, the name Warren Zevon merely equates to the American singer-songwriter’s one and only hit in the late 70s, “Werewolves Of London”. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, as it’s a great song and Zevon deserved his pop-star moment. Things is there was more to Zevon’s long and varied career than that one song. Much, much more.

Arriving on the New York folk scene in the early 60s at the age of 16, Zevon spent the 60s trying his hand at being a writer for hire, then became half of folk duo Lyne and Cebelle and recording a debut solo album with Kim Fowley in the producer’s chair. After the album bombed and its follow up never saw the light of day, Zevon became the band leader for the Everly Brothers, before helping Phil and Don launch their respective solo careers in the early 70s.

The pull of a solo career didn’t elude Zevon for long though and after a brief sojourn living in Spain, he returned to California, became a flatmate of the then unknown Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham and fell in with the rest of a Californian music scene which consisted of The Eagles, Linda Ronstadt and his frequent collaborator Jackson Browne. It was Jackson Browne who became the key figure at this stage in Zevon’s career, as it was Browne who convinced Elektra to sign Zevon, becoming a regular touring buddy and he then went on to produce and promote his self-titled album.

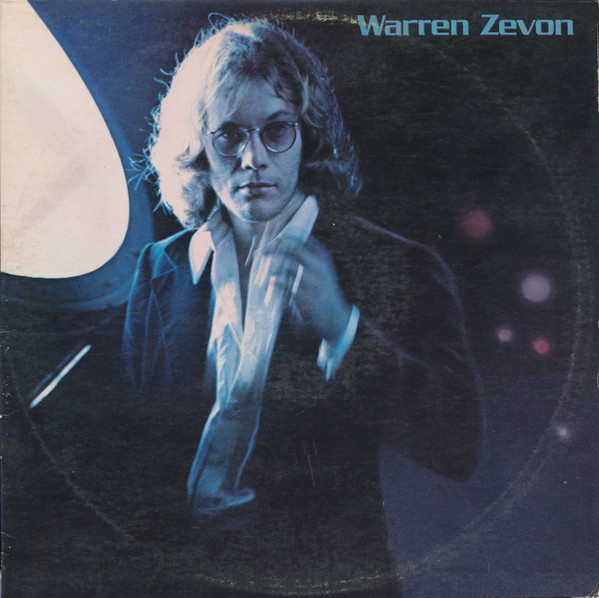

Warren Zevon is a brilliant album and seemed to have just about every major name from the California rock scene guesting on it somewhere. Even at this stage in his career it was evident that Zevon was in a different league to his contemporaries as a writer, as the album boasted unparalleled songs like “Frank and Jesse James”, “Hasten Down the Wind”, “Poor Poor Pitiful Me” and “I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead”, all of which underlined the fact that he wasn’t afraid to admit that he had already experienced the downside of fame and was able to mould those experiences into killer lyrics and great tunes. Best of all though was the album closer “Desperados Under the Eves”, an epic hymn to his struggle with alcoholism.

As an album Warren Zevon hailed the arrival of a major new talent and one that in the bloated singer-songwriter scene of the late 70s only had Randy Newman as his peer. Both Zevon and Newman were able to blend darkness and humour into their lyrics, but Zevon was far more the hedonistic rocker than Newman ever was. As a result Zevon, while made friends fast in the American music scene, he had already gone a long way to succumbing to its dark side. Actually, scrap that, he didn’t just succumb to it, he actually embraced it.

Following up Zevon’s major label debut couldn’t have been an easy task, but it’s no accident that it’s follow-up, Excitable Boy, became Zevon’s best known and biggest selling album. Just the fact that it featured the aforementioned “Werewolves of London” would have been enough to ensure big sales, however it also featured some of the strongest songs that Zevon would ever write, with the title track, “Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner” and “Lawyers, Guns and Money” confirming that “Werewolves…” wasn’t just a freak hit single and that Zevon’s writing continued to have a breadth and depth that his contemporaries could only aspire to. That said, the album also had the first hints that Zevon wasn’t beyond recording the odd album filler, but when he was at his best he was still untouchable and as a result Excitable Boy was a sizeable hit on the American album charts.

Already the cracks had started to show though. The next album, Bad Luck Streak In Dancing School, saw Zevon further water down his potency by featuring far too many throwaway tracks throughout the album, even resorting to the novelty tune “Gorilla, You’re a Desperado” in an attempt to emulate the success he had with “Werewolves…”. There was good stuff on offer for sure, such as his collaboration with Bruce Springsteen, “Jeanie Needs a Shooter”, but you can’t escape the feeling that Zevon just wasn’t trying as hard anymore. That said, on a good night Zevon could certainly still deliver in a live environment, as ably demonstrated with the blistering live album Stand in the Fire, a recording of a club gig where you can literally hear the paint peeling off the walls, the sweat drip from the ceiling and it sounds for all the world like Zevon is possessed during at least a third of the performance.

By the time Zevon released The Envoy in the early 80s, mainstream interest in him was starting to fade, and despite all the evidence that he was continuing to mature as a songwriter, he was continuing to struggle with personal demons along with trying to find his place in a rapidly changing music scene. The Envoy would be the last Warren Zevon album for a few years and he would gently fade into obscurity to battle his addictions.

By the time Sentimental Hygiene was released in 1987, Zevon had signed to another major label, become close friends with R.E.M., then the hottest young act in America and the album once again found Zevon sharing the studio with big name guests. Despite the heavy-handed 80s production methods used, it was an effective come back album and re-established Zevon as, if not a major act, then at least an interesting one. His songwriting had continued to mature in his absence from the spotlight and songs like “Boom Boom Mancini”, “Detox Mansion” and “Even a Dog Can Shake Hands” showed that he was still able to pen a classic tune. Zevon had pulled off an impressive come back and the world was once against his oyster. It was just a shame that the follow-up album, Transverse City, despite the guest appearances by the likes of Neil Young and David Gilmour, was a bit of a mixed bag and he once again found himself getting dropped by a major label.

The 90s found Zevon in somewhat reduced circumstances, on a small record label, recording with a tiny budget and a stripped down band. In some ways this may have focused his songwriting and a number of songs on Mr Bad Example demonstrated that on a good day, he could still pen a classic tune. On stage he usually played solo, switching between guitar and piano as each song dictated, which I suppose gave him a greater flexibility with his setlists and developed a stronger bond between Zevon and his reduced but ever loyal audience. In the mid-90s, an album called The Mutineer sneaked out and barely registered a blip in sales. Thus it seemed that Zevon would spend the rest of his days performing to small audiences and putting out albums whose sales never matched his talent.

By the opening of the new millennium, Zevon seemed oddly comfortable with his place in the musical firmament, which maybe went some way to him recording Life’ll Kill Ya, an album which found him comfortably adopting the mantle of elder statesman while considering his own mortality. It also didn’t hurt that it was his best album for two decades. Songs like “I Was in the House When the House Burned Down” and “For My Next Trick I’ll Need a Volunteer” are slices of prime Warren Zevon material and the trio of songs that found him ruminating on death (the title track, “My Shit’s Fucked Up” and the beautiful closer, “Don’t Let us Get Sick”), ably demonstrated that age had eventually brought both wisdom and creaking bones, as well as broadening his streak of black humour.

The follow-up album My Ride’s Here once again found Zevon distracted by the passing of time, though sadly it didn’t quite reach the rediscovered heights of the previous album. There were still stand out tracks like “You’re a Whole Different Person When You’re Scared” and “Genius”, and even had David Letterman yelling out ‘Hit Somebody!’ throughout “Hit Somebody! (The Hockey Song)” (David Letterman had actually been a part of Zevon’s life for a while by this point in his career, Zevon having frequently guested on Late Night and had even stood in as temporary band leader on the show from time to time), but given what he had previously proved he was still capable of, it was a little disappointing.

It was a little while later that life started imitating art for Zevon. In a strange reflection of his previous two albums, a lifetime of avoiding medical check ups had caught up with him and he was diagnosed with inoperable cancer which had been caused, not by his previously hedonistic lifestyle, but by, of all things, exposure to asbestos. Whether Zevon suspected something had been wrong with his health for some time, thus inspiring him to write his recent material, is a matter of debate. Whatever the case, his card was marked and rather than try and delay the inevitable, he threw himself into recording one last album.

It’s a measure of how well thought of Zevon was among his contemporaries that the likes of Jackson Browne, Tom Petty, Bruce Springsteen, various Eagles and other big names from the American rock scene turned out in force to help him record The Wind – There was even a VH1 special made about the recording, though it wasn’t broadcast until Zevon’s passing. The Wind was a good album given Zevon’s failing health and the unique situation he found himself in seemed to focus his writing once again, resulting in a number of great songs, among them the stunning “Keep Me in Your Heart for a While”. During the recording sessions he went out of his way to do one last Letterman interview, on which he advised the viewers to ‘Enjoy every sandwich’ and he would perform “Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner” one last time. It would be his last public appearance.

Warren Zevon died on September 7th, 2003, barely two weeks after the release of The Wind. In an odd little epilogue, it would be the only one of his albums to ever chart in the UK.

Looking back on Zevon’s career, it’s easy now to view him as a flawed and self-destructive genius. He wrote some amazing songs, but then he also allowed lesser quality material baring his name to be released. He was well loved by his contemporaries, but battled addiction and struggled with family relationships throughout his life. It is perhaps a measure of Zevon’s self-awareness that on receiving his terminal diagnosis he specifically instructed his ex-wife to write a brutally honest biography of his life. It was published in 2007 and some of the unsavoury revelations within surprised even those that considered him a close friend. While no one would ever claim that he was an angel, Zevon himself seemed to revel in his own brutal honesty.

It’s 17 years since Zevon’s passing, and we can only wonder what he may have achieved in those years if he had lived. Many of Zevon’s contemporaries have enjoyed renewed interest in their careers due to long-winded and sycophantic record-label financed documentaries being made about them. Part of me would like to think he would have resisted that, but then again he would have been one of the few to have genuinely deserved it, as he remained a of compelling character until the very end.

No Comment