MY ROUTE into The Jasmine Minks and the whole world of early Creation Records – Slaughter Joe, Biff Bang Pow, Revolving Paint Dream and so many others?

Mine was the time-honoured one: that is, the combined good agency of a friend’s older brother and the humble cassette. It’s a story repeated everywhere there are older brothers into music, I’m sure. I didn’t have one, myself, so I relied on other people’s. A brother, that is. And so unfolds the tale.

Actually, although this older brother influence on my musical development had been at play a year or three, it hadn’t been entirely successful so far; in sonic patrilineal succession the older brother had invariably passed down to the younger brother and thus into my formative cultural aesthetic sense stuff which, in retrospect, quite stank the place out.

Let’s call two of these friends of mine Richard and Edward for the purposes of this piece, and mainly because that’s what they were actually called; their siblings were a few years on down the line, into the world of freshers’ years and BBC Micros, for serious, working on-type stuff, and what I dimly and possibly erroneously recollect as physics and architecture degrees, respectively. Thus, tapes would be handed down, vinyl (memorably once, an album picture disc) temporarily purloined for the afternoon or if they were out for the weekend.

And so we’d gather round these circular musical artefacts. And so into my world came Asia and Rush, and Yes, and Barclay James Harvest. Hmm.

Now, I won’t say I quite hated it, exactly – my critical faculties and self-confidence weren’t that developed; but under my own lonesome steam as a tweenager I’d found The Jam, been bought that super-long (30 tracks!) cassette of Snap! for Christmas; also Two Tone – OK, all of which was right there in your face on Top Of The Pops; Echo & The Bunnymen, the spellbinding blast of whose “The Back Of Love” I had to get WHSmiths to order in for me like, specially, as in the small top 40 section upstairs in the record department of my town’s branch they were wise or cynical or both, and never bothered ordering in the singles that scraped to no.36 one week to sit unbought and be wheeled out in the bargain bins for like, 20p in the ensuing months.

And Asia and Yes, &c – they weren’t quite like that. They were from … another thing. Something a little flabby, a little removed. Nothing, I knew, to do with my world.

(Honorable mention must go at this point to Rob, whose older brother was big into hot-rodding and bike-modding and greasy jeans, and whose attempts to foist ZZ Top and, for some reason mysterious to this day, Brit prog-jazz-funkers If onto us, were always rebuffed – Rob by this juncture already having discovered The Smiths).

Actually, I had had my first actual baptism into the ways of Creation Records a few months before the cassette – I just didn’t know it at the time. I’d attended someone’s 14th birthday do at the local Catholic hall, a night of rites of passage; two much older lads – I mean one of them must’ve been 17, bejesus, definitely shaved – commandeered the little sixth-generation Dansette or whatever and unleashed this fucking wall of noise, just screaming feedback, with other distorted guitars and some echoing vocal deep in the mix. It was, of course, the Mary Chain’s “Upside Down”. Except there was no way sheltered little me could’ve known that. And I certainly wasn’t gonna approach the scary older guys, all in black and whirling like dervishes to this delicious, unholy fucking screech in a suddenly emptying Victorian hall. No way, Jose.

(Later, of course, the two and I would become good friends; also at that party, which was a rite of passage in a Breakfast Club-meets-Sid And Nancy way, I encountered my first person with a bag of glue over their head, and witnessed, in real time, my first ever blowjob. It also transpires, during some fact-checking for this article with the elder of the two brothers that later on at that party they went head to head with the son of a local NF organiser, who was teenage drunk and spouting racist nonsense).

No, it was Martin who brought the breakthrough. Martin, who was in my year at school and who had recently hustled Rob, a bit of dab hand with the drumsticks, to join his band. Martin, the first real encounter with whom I recall as him slamming back the compartment door on the train, carrier bag of new records in his hand, stomping the snow from his 14-hole DMs and, gesturing at the rapidly melting mess, exclaiming: “Well, that’s Thatcher for ya.”

Martin wore a German army coat and black jeans with turn-ups and had a Mary Chain flat top and badges for bands I’d never heard of. He’d also been in a band, an actual garage band, who rejoiced in the name Dead Men Don’t Kill Armadillos (hey, don’t blame me, I but report this stuff) with his older brother and some guys from the years above, including, it transpired, those whirling monochrome lads from the Catholic hall.

He’d done Rob a tape, which he’d taped off his brother, which in turn Rob taped for me: it was two of those really early Creation comps, Wild Summer, Wow! and Different For Domeheads, and suddenly, even at a William Basinski-like fifth remove from the original fidelity, a whole new world of bands no one had ever told me about opened up: they were a little ramshackle and sometimes wavered out of tune and they were called things like The Weather Prophets and The Pastels and The Loft. But the songs, the aesthetic. the sentiment … these I loved.

But the song that really enraptured me – hell, that wasn’t part of either album; tape being the valuable communicative resource that it was, every second was stuffed with tracks, so many that you had to write well past the allotted space on the cassette cover and either right down into the folds and the thin cradling lip of the case or take a gamble and start wonking the track titles on up around the side margins, around the top; down the other side, even. Cramming them in. So there were other Creation singles and even some Fall and definitely that standby for remaining seconds of unfilled tape, Ivor Cutler (“I’m Happy”, probably) – and there it was, the song I completely fell for; it was called “Cold Heart”, and it was by The Jasmine Minks.

Now, all the information I had to go on was there in spidery Biro; nothing else. There might not even have been anything else in the world at all to know, for all I knew. This cryptic C90 became my world. A good three years or so past puberty, I was also the same distance past fantasy trilogies; but these names. The Weather Prophets. They must have special powers, surely. And The Jasmine Minks? The what, now?

The twin voices in call and response on “Cold Heart” – a lantern-lit tale, one voice mellower, more mellifluous, the other higher, crisper – must belong to furry creatures possessed of human attributes, like some indie band Wind In The Willows thing, I thought. (Still sorta do). “Cold Heart” came to me as a miniature spell; rural, unhurried, those great call and response vocals between the singers I now know to be Adam Sanderson and Jim Shepherd, and also somehow a whole lot longer when you were inside it than the bare four minutes it was – mind you, in the spirit of the age, that’s almost as long as labelmates Primal Scream’s entire “Crystal Crescent” 12″ – that simple, organ-underscored chorus “Cold hands, warm heart, my dear”; that languorous guitar break which suddenly ups the vim and becomes this beautiful, liquid run across the strings with hammer-ons and … stuff; they were even explicitly self-referential, talking of the revenge of the Jasmine Minks. Why? And against whom?

Clearly, some serious record shopping needed to be undertaken.

Now, for all the remoteness of rural Cornwall at that time – a hundred miles (still is) from the nearest motorway and then with barely any dual carriageway at all in the long miles preceding, we had one oasis of recorded music cool – Soundcheck, the most westerly outpost of the Chain With No Name independent distributors’ network. Situated in a tiny terraced cottage at the very northern end of Penzance’s shops, it was somewhere I visited with increasingly regularity and my pennies as I got to know Martin and these weird music heads. Sometimes we’d even get the train down mid-morning, grab a pastie and chain smoke on a bench outside until the van of that week’s new releases pitched up, late lunchtime. Another fag and we’d line up at the counter, demanding to know what was new in, boxfresh.

We’re obviously talking pre-tinterweb and a place even further removed from that London – from anything with a real beating heart, than now; no lightning quick touch-of-a-button ordering. Our town had this little group of maybe a dozen or so indie kids, many with flat tops, all with DMs, some very much championing certain bands or scenes – Felt, or Flying Nun – but there was us, the people who made these records, Soundcheck, and that was the map complete. Oh: and a couple of goths, who’d cover themselves in flour to look like the Nephilim.

Though unbeknownst to us Harvey Williams of Another Sunny Day and later The Field Mice was down there in Penzance, too, we never met, there being no socials on which to; and Aphex Twin was tucked away among transistors and wires four miles in the other. An early incarnation of The Family Cat was practising in a village hall nearby; Truro was, eternally, a little bit too cool for skool, came freighted with the arrogance of having a cathedral way outsize the needs of the small Georgian market town it actually was; people wore salmon-coloured trousers there. If we ever pitched up at a party in TR1, we’d inevitably end up sat on the fire escape. Helston, by contrast, seemed to be mostly populated by huge strapping fuckers into Zep and New Model Army with clogs and crimped hair. The music, cliche or not, was a lifeline.

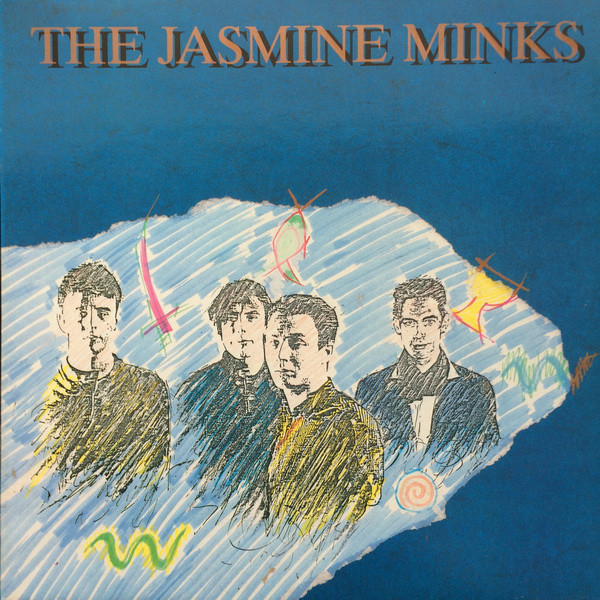

And it was on one of my very first visits to this new mecca that I took the plunge and paid £4.29 or something for The Jasmine Minks’ self-titled album. Gold, serifed lettering against a grand, dark blue, with a stylized tear revealing monochrome portraits of the actual band, who were human it turned out – tastefully scribbled and squiggled over in pastel tones. Hey: it was the Eighties.

By this time I’d learned a little about them. Like labelmates The Pastels and The Jesus And Mary Chain, they were Scottish. From Aberdeen, even, which was like, literally hundreds of miles away and impossibly exotic, and it had an oil boom, so was the exact opposite of my town, which was raking through the final ashes of tin mining; but it was a granite town, so in an architectural sense exactly like mine, too, in a way.

And I learned this, not all at once, but down the years: they’d formed in 1983 and signed to Creation pretty quickly, actually becoming one of the label’s early genuine success stories, with “Think!” garnering a Single of the Week accolade in the British press, and quite rightly too – fizzing and polemical, it moved a modish mod sound on and was so full of energy, it sounded like the band had been a coiled spring just waiting for this unleashing. The majors courted them, in a small way; a gig at McGee’s The Living Room caught a lackadaisical press on the hop; there was a six-track mini-album, One Two Three Four Five Six Seven, All Good Preachers Go To Heaven, which was great and it snarled at you and it took me years to get my mitts on one.

The album I was treasuring had been recorded in the small Aberdeenshire town of Ellon on a budget of just £600; the focus was on a low-budget, high-quality song-based album, which was just as well, really, given that cheque. So, just 0.0024% of a Loveless, if the rumours be true.

And what an album. It begins with the heralding, wired rush of “I Don’t Know”, twelve-string chords striking brightly, a busy, melodic bassline and a lyric at a loss with an amour and the world at large, a world about which “the papers won’t tell me”; it breaks down to a bass before sizzling back in on brass, all 131 seconds of it. And then? “Cold Heart”. Jesus. See above.

And if that hadn’t completely seduced you, here was “Choice”, a perfect nugget of mod-pop, call and response vocal so deft, a real dialogue, with that poetic refrain which asks questions, possibly of the great, final reckoning: “These days, I’m looking back / Trying not to turn / To salt.” , a summing up, a totalling, and in keeping with a elegiac tone that pervades much of the record. Even then, things were better before. As with “Cold Heart”, there’s a feeling of really massively wishing to return to a something or some things now unattainable, not necessarily explicitly stated but wafting through, a triggering scent caught on the breeze, revisited in tone throughout, in the way you draw emotionally from Bill Fay’s debut album as well, I’d later discover.

“Ballad Of Johnny Eye” will always be, to me, a winter’s dusk captured in a steamed cafe window: one of those dusks, like now, let’s be clear, when its really fucking bitter and you just do not want to be outside and people genuinely scurry to the bus, clutching at scarves and hats, Lowryesque. It has romance if ever a song did, if somehow again yearning, resigned, twelve-strings chiming, the massed hookline of beauty and bleakness, “I wish I was the air / So you could breathe me in, and hold me there,” ringing out before this brilliant, skirling, Byrds-like lead break that ups through the scales and which took my mate CJ many weeks to unpick – and boy were we ever impressed when he unleashed it for the first time in his Mum’s living room on the Rickenbacker he’d cashed in his life insurance in for. And there’s that poetic repetition of the demotivated, the paralysed: “So I sit in my chair and I sit in my chair”. Paralysed by the weight of it all, remote control and a tinnie, walls anaglypta and a little nicotined, is what I always picture.

The pop bouncealong of “Work” reprises the theme of pointlessness and rebellion first visited on the fiery “Work For Nothing” with telling lines: “And if you work for 50 years / “They slap your back, buy you a couple of beers”. In the context of the album it’s a throwaway couple of minutes of fun, and it does, I think, get overshadowed by a whole clutch of other tunes; but it is a little gem – excise it and get it on a tape, I mean a playlist, and let it breathe.

Because then comes the grand proclamation of “Forces Network”, and I always imagined the band playing this at some dreich cluster of MOD transmitters on a lonely Speyside hilltop; there’s a post-Falklands anti-militaristic tone, and why wouldn’t there be, with lines like “leave the girls and take the boys to play / On violent fields”. It appears in a different version to that which graces the flip of the “Cold Heart”, here gussied up with added snarl, chords yawing like the pitch of a troop carrier in the grey foam of the South Atlantic. The YouTube link for that one is up above there, if you’d care to scroll.

And two of the album’s greatest moments are out here on the second side: “Painting/Arguing” and the closer, “Cry For A Man”. The former is one of those great tunes which refuses to reveal its secrets at first or even tenth listen, from the title down. Who’s painting, and who’s arguing? What is this adjectival interplay? It’s a quiet masterpiece of arrangement, too; somewhere inside it beats baroque pop of the Emitt Rhodes/Pearls Before Swine variety. It begins in a slow bass and lyrics also blurry and impressionistic before shifting gears in the twin attack of that trumpet and one of those unbeatable one-note lead guitar lines, high up the neck in a rousing chime, against which the trumpet interjects while the bass busies in the spaces in between. It’s completely oblique, a piece of very grown-up songwriting and also hugely danceable.

Then that closer, the tenth song of ten, “Cry For A Man”; a proper finish to a record; diurnally it feels like a song for the end of the day, a bringing together of the album as a whole in one last rally, bass unfurling deftly, a two-note guitar chime, ba-boom! type flourishes of vocal and trumpet; and then, just past the middle eight, it does this unexpected thing and accelerates in a big crescendo sweep of brass and an increasingly insistent lead line that just gears up and up and up in mod pop brilliance.

And in my mind’s eye I’m in my friend’s bronze Morris Ital (and there’s a forgotten product of the ailing UK motor industry); we’ve been out for a jaunt to scenic spots, just kicking about and having a giggle; there’s the nimbus-grey skies of a slightly shitty May Sunday, and we’re on the way home, sweeping around the frowzy collection of net lofts and ancillary buildings and weighbridges in a nearby former port town that would soon be bulldozed by a local entrepreneur and remain wasteland until the advent of bravely overdesigned Asda slab more than two decades later.

And as I recall it through the flawed prism of memory, I’m actually up with the gulls with a birds’s eye view down on it all, one final time before the bulldozers move in; another nothing-to-report Sunday teatime but “Cry For A Man” is playing on the stereo of a car and I’d lofted into epiphany with the song and the folks would be at home and tea would be on the table pretty promptly, cos, y’know, they were still alive then. And in that moment everything was perfect, and perfectly alright.

The Jasmine Minks’ The Jasmine Minks only got the one, solitary pressing on vinyl, back in 1986; you can still pick a decent copy up relatively cheap, and although prices are starting to climb it’s nowhere near the levels of £££ currently commanded by some other Creation releases, thankfully. If you’re of a CD persuasion, it got a twofer issue with One Two Three Four … in 1990; but maybe your best bet currently is Cherry Red’s 2xCD compilation Cut Me Deep: The Anthology 1984-2014, a whole 48 tracks that includes almost this entire album, with scores of other treats besides.

Do it. Having The Jasmine Minks in your life makes so much sense.

No Comment