There are some albums that don’t just define an act’s career, or a moment in time, but a whole musical movement. It’s those albums where the act haven’t just pushed themselves creatively, but have comprehensively outsmarted each and every one of their contemporaries and produce a musical statement which the listener doesn’t just go ‘Wow, that’s fantastic’, but is forced into stunned silence as they try and comprehend how anyone could possibly create music as startlingly breathtaking as what they are listening to.

By 1972 Progressive Rock was the dominant musical style being played by middle class white blokes here in the UK (and indeed across the rest of Western Europe), at least when it came to the album format. While Heavy Rock was also doing big business in terms of album sales, that was down to a handful of absolutely huge acts, it simply didn’t have the diversity of sound that Prog had, while the single charts here in the UK were studded with sequins and smothered in glitter. The thing is, even prior to 1972, Prog Rock was in significant danger of becoming far too bloated and self-important, with a annoying tendency for technically brilliant musicians to try and impress the listener with how they were playing the music rather what they were playing. This over-reliance on demonstrating musical technique in favour of actual tunes meant that Progressive Rock was becoming more and more about technical wizardry as opposed to good tunes. Another thing the Prog Rock often struggled with was relatable lyrics. With a few honourable exceptions Prog Rock spent too much time indulging in lyrics informed by whatever science fiction or fantasy novels their lyricist was reading at the time. True, Heavy Rock had a tendency to do that too, but at least the listener was in little doubt that those lyricists had been reading the abridged large print additions, while the Prog Rockers had got themselves lost in every minute detail within the appendices.

Jethro Tull had spent their first few years as critical and commercial favourites here in the UK, in which time they had topped the album charts and issued a brace of singles which had neither been love songs, or standard sci-fi/fantasy nonsense. Aqualung, the album which had seen them make significant inroads into the American market, had balanced heavy rockers with lighter acoustic numbers, and had consisted of songs which detailed tales of society’s outcasts and criticised organised religion – pretty down to earth, yet heavyweight stuff for Prog Rock. Some hailed it as a masterpiece of a concept album, which prompted Tull frontman and creative dictator Ian Anderson to point out that, while some of the songs were thematically linked, it wasn’t intended to be a concept album.

Concept albums had long since been considered the format that all Progressive Rock acts should aspire to, as the sci-fi and fantasy lyrical elements frequently easily translated into a continuous narrative arc. Some Prog Rockers had taken the idea one step further and instead of every individual song in the album adding to a conceptual narrative arc, they had started to fill entire sides of albums with one track that would inevitably stretch what otherwise would have been an enjoyably economic and punchy track, to uncomfortable lengths by crow-barring indulgent solos from each band member. Concept albums were therefore already becoming bafflingly complex musical white elephants, yet they continued to be critically lauded, which encouraged earnest young men in beards and greatcoats to continue to record them, because that’s what they thought the people wanted.

Realising that so many of their contemporaries were all trying to outdo each other by releasing ever more complex and ornate concept albums, Jethro Tull, a band which had always had a definite element of humour, decided that the time was right for an album that gently lampooned not only their peers, but the music industry that encouraged them to create such ridiculous musical statements, the listeners that lapped them up, and Progressive Rock itself. To underline just how serious they were about pointing out how ridiculous the situation had become, Anderson and his band mates set about recording a concept album which consisted of just one single song, split into two only by the sheer necessity of having to flip over the vinyl. Anderson has since admitted that it was Tull’s intention to record ‘the mother of all concept albums’, and well over four decades later, anyone listening has to agree that they over-delivered on every possible level.

Thick as a Brick starts with a circular acoustic guitar riff from Anderson, which expands into one of Jethro Tull’s most accessible tunes, which served double duty as effectively a radio trailer for the entire album. The playful acoustic opener is then blasted away by some gloriously explosive hard rock guitar work Martin Lancelot Barre, reminding us that Tull were always a rock band at heart and delivering just the first of the album’s first significant changes in pace. One of the strengths of Thick as a Brick is the fact that, while the extended song and concept format gives the entire band room to stretch out, they never once loose sight of the fact that they need to keep the listener engaged. To do this they regularly loop back to the original circular acoustic guitar riff, or reprise an earlier part of the album in order to refocus and keep the album sounding tight and disciplined. That’s not to say that the band don’t get chance to demonstrate their individual virtuosity though, as in addition to his vocals, Anderson expands his musical armament beyond his flute and acoustic guitar to all manner of wind instruments, while Martin Barre’s guitar runs rampant throughout, Jeffrey Hammond Hammond proves how far he has come since Aqualung, an album Tull recorded while he was still learning to play the bass and keyboard player John Evan, who had already established himself as a key element to the band’s sound by Thick as a Brick, continues to impress throughout the album. Perhaps the biggest revelation though is the drum work of Barriemore Barlow, who had replaced Tull’s original drummer Clive Bunker since Aqualung. Barlow’s drumming throughout his time with Tull was superlative (no less an authority than John Bonham acknowledged Barlow as one of the supreme drumming talents of their generation), particularly on stage, but the very nature of Thick as a Brick means that he is given more spotlight than on any other Tull studio album. Another special mention needs to go to Tull’s long time collaborator David Palmer, whose orchestral arrangements enhance rather smother the album, something which had blighted so many Progressive Rock albums released in the early 70s.

Perhaps the secret to Thick as a Brick’s success is the fact that, for all it’s ambitious arrangements as it skilfully sweeps from acoustic ditty, to hard rocking, and every point inbetween, it is executed beautifully, but you never get the feeling that Jethro Tull were taking themselves so seriously that it was at the detriment of creating the best album they could. This well considered lightness of touch means that Tull skilfully avoid allowing their humour to tip over into outright silliness, something which just about every other Prog Rock act did if they tried too hard to convince the listener that they possessed a sense of humour (check out ELP’s “Benny the Bouncer”, or Pink Floyd’s “Seamus” for two particularly excruciating examples of this). While Thick as a Brick certainly has its more throwaway lyrical conceits (references to Biggles and queuing in the office canteen), it is musically a seriously accomplished album, which given that various band members have since confessed that it was written and recorded on the hoof on a day by day basis, is no small achievement, and an enduring testament to the benefit of not over-thinking things. The album works because Tull crafted it with the intention that the listener was in on the joke, and they would understand that the whole things was a spoof of over-inflated, self-important concept albums made by skilled musicians who really should have known a lot better.

Uniquely hook-laden for an album length song, Thick as a Brick remains a rare example of an extended song suite that remains nicely accessible throughout. Where there are instrumentals or solos, they avoid the ridiculous macho posturing that was so fashionable at the time, in favour of something a whole lot more playful and, frankly, clever. There is no point of the album where it feels that Tull are labouring the point, or sodding about for the sake of sodding about, and even in the places they loop back to themes and hooks present earlier in the album, it is done in such away that it acts as a musical thread that ties the whole album together and avoids it becoming a disconnected mess of half-baked tunes.

Lyrically Thick as a Brick is a thing of wonder, as again themes and choruses are recycled and remodelled throughout the album, with Anderson often subtly subverting the original version to make an entirely different statement. While most of Tull’s peers put musical ability before great lyrics, Anderson was one of the most unique and individual writers of his generation, leaving the lyrics ambiguous enough for anyone listening to put their own spin on proceedings. That said, the conceit that the lyrics for the whole album was actually written by a prodigiously talented eight year old (and the fact that some people actually still believe that), is just another mark of how well executed the entire project was.

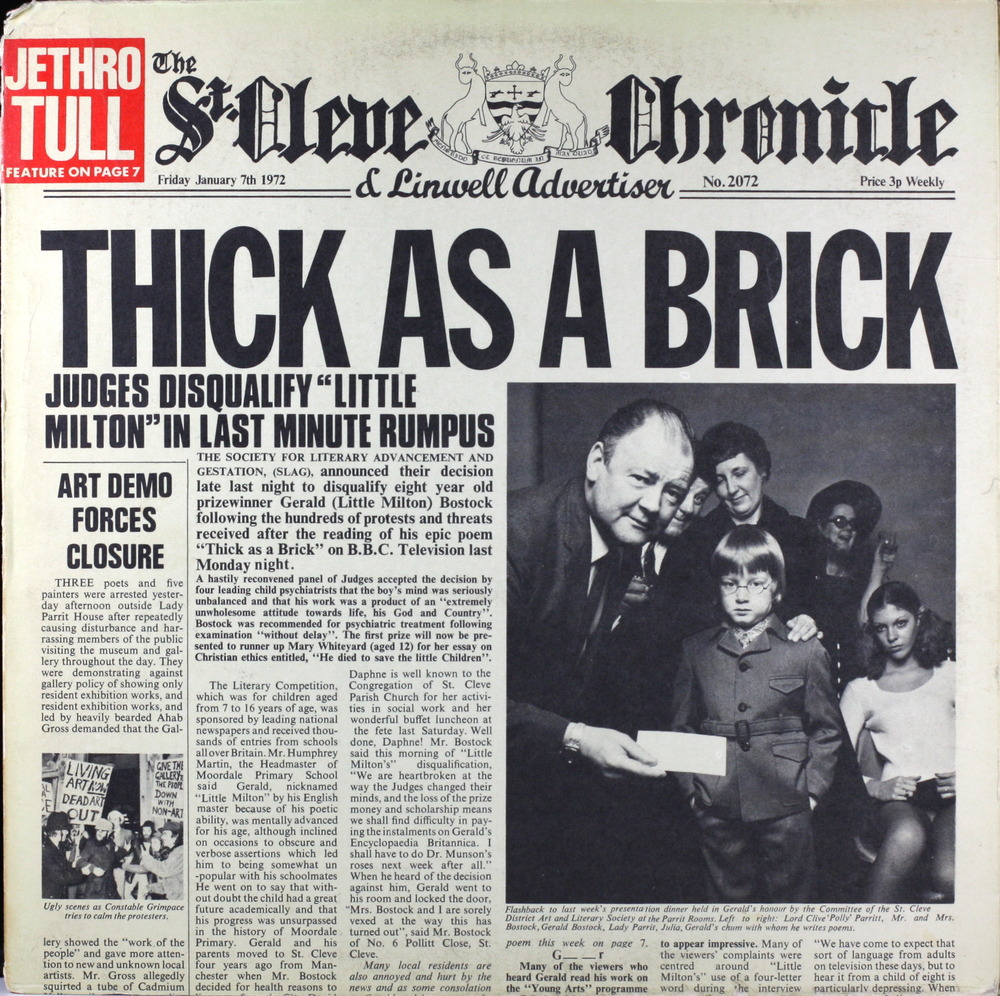

If the music of Thick as a Brick is a roaring success, then the album’s original packaging, in the form of a parochial broadsheet newspaper, sweetens the deal even more, to the fact where it’s possible to get lost for hours in the spoof news stories (with a scandal about the aforementioned eight year old as the front page headline) full of in jokes, puzzle pages, a short story, an amusing review of the album itself and some bizarre wanted ads. Apparently written in hilarious comedic detail by the band members, it effectively invented what we would these days refer to as meta-humour. While the slew of reissues of Thick as a Brick have made various successful and unsuccessful attempts to replicate the impact of the original newspaper cover, in truth the size of CDs has meant that it has always been a watered down version of the original.

For all of Jethro Tull’s careful planning and frank openness about Thick as a Brick, something they perhaps couldn’t have foreseen was how many music fans just didn’t get the joke and took the album seriously as a straight faced attempt at pomp-rock. With the album hitting the top of the American charts, as well as doing big business in Europe, it proved that Thick as a Brick worked on the level of being a fantastic example of accessible, yet complex, Progressive Rock, as well as a stunningly well executed parody of the same.

If you’re someone that has always considered Progressive Rock to be music by self-indulgent individuals with an excess of talent, but a deficit of good material, then I would encourage you to acquaint yourself with Thick as a Brick. Impressive with being excessive, smart without being smarmy and droll without being silly, it’s all the great things about progressive rock, without any of the stuff that dragged genre down, Thick as a Brick may very well be the greatest concept album of all time, which given that it was basically done as a bit of a laugh, is no small achievement.

No Comment