When the broom of Punk arrived to sweep away the dust bunnies of the old guard, Jethro Tull took the frankly baffling route of going folk-rock. Having been born out of the 60s British Blues Boom, they’d already undergone an evolutionary career which saw them dabble with hard rock, satirical concept albums, art-rock and even flirted with the idea of stage musicals. Quite why they decided that the arrival of a bare-boned and aggressive youth culture was effectively the signal for them to go morris dancing is anyone’s guess, but looking back, it’s evident that such a move allowed them to survive the onslaught of punk while so many of their contemporaries fell foul of the next big thing.

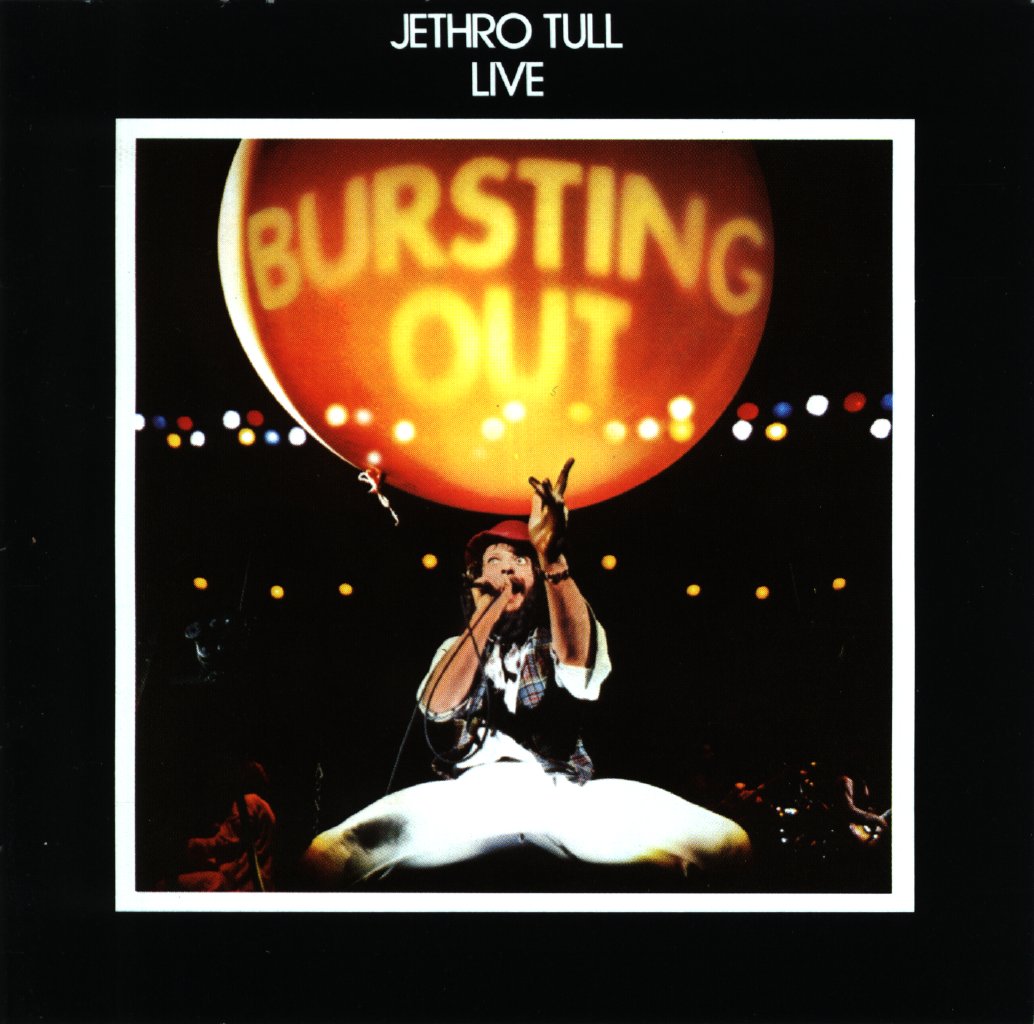

In truth the three studio albums recorded during this period are a mixed bag, but Tull were undeniably at a live performance peak. Having established themselves as one of the biggest live acts of the decade and undergone a myriad if line up changes, by 1978 they had a wide range of material and were a musically slick unit that could play almost any other big-name rock act of the stage. A handy time then to record and release their contribution to the catalogue of live double albums, Bursting Out, and providing incontrovertible evidence that while other acts were bigger, few knew how to entertain in the same way as Jethro Tull.

Following an enthusiastic introduction by Claude Nobbs (the same Funky Claude that Deep Purple had immortalised in “Smoke on the Water” a few years previously), Bursting Out opens with Martin Barre’s guitar screaming into life and one by one each member of the band joins a cacophonous intro to “No Lullaby”, a song from the then new Heavy Horses. While the studio version of “No Lullaby” is a weighty track, on this live version Ian Anderson manages the neat trick of sounding confident, yet oddly sinister, and the way the whole band segues into an amped-up reinvention of “Sweet Dream” is breath taking, allowing Martin Barre’s colossal riff to take centre stage. In the often heated, yet utterly fruitless, debates about great guitar heroes, few music fans outside of Jethro Tull fanatics ever mention Martin Barre, however when it comes the same discussion being had among other rock guitarists, his name is mentioned more frequently than you’d expect. Often kept on a tight leash in the studio by Anderson’s production techniques, on Bursting Out, Barre demonstrates that he belongs at the top table of six string maestros once and for all and this hard rocking “Sweet Dream” is arguably the definitive version.

After the opening salvo. Anderson introduces the individual band members in typically jokey fashion before a short brace of semi-acoustic tunes. Anderson’s between-song patter has always been a feature of Jethro Tull gigs, to the point where how much you can either appreciate or forgive his humour often has a direct influence on how much you enjoy the band in a live setting. While it’s often good natured, certain listeners may find Anderson’s joking around grating, given that it’s preserved forever on Bursting Out. Something you can’t criticise Anderson for is his stage craft and his ability to connect with this audience, as one of the more idiosyncratic of rock’s frontmen, he’d honed his stage craft to perfection by this point, offering a unique counterpoint to the preening pretty-boy frontmen that typified his contemporaries.

One of the benefits of Jethro Tull waiting a decade before they released their first live album was the sheer range of material they had to build a set list around. While their studio albums in recent years had taken a more folky direction, the emphasis was still very much on being a rock band, so space is still found for a “New Day Yesterday” from their blues-rock period, a much truncated blast through “Thick as a Brick”, which still makes it sound like the definitive prog rock epic, as well as crowd pleasers like “Too Old to Rock’n’Roll; Too Young to Die” and “Minstrel in the Gallery”. Always much more of a hard rock proposition in the flesh, this is the sound of a well-drilled, searing rock band at the top of their game and energy levels. Playing particularly well is drummer Barriemore Barlow, who finds the elusive sweet spot between ferocity and technical playing and stays there throughout the gig, ensuring that every tom fill and drum roll he performs would baffle a lesser player. Much like Barre’s guitar work is feted among other guitar players, Barlow’s drumming was held in particularly high esteem by no less an authority in pounding the skins than Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham. That’s not to say that Barlow’s brother in rhythm, John Glascock is slacking. Often regarded as the most gifted bass player Tull ever had, Glascock’s supple bass runs are highlighted throughout the album, and are just another reason that this is the line up that recorded Tull’s definitive live album.

Of course, this being a 70s live album by one of the era’s premium rock bands, there’s a couple of extended instrumental passages featured on Bursting Out. The first is a much expanded “Bouree”, effectively giving Anderson an opportunity to show off his raw and untutored flute technique, and letting piano player John Evan and pipe organ player David Palmer show off their not inconsiderable ivory-tinkling skills. This dual-organ line up had help make Tull a unique proposition since the mid 70s, and it was on a live stage that it really let the band stretch their legs, as well as allowing Evans and Palmer’s on stage characters to contrast each other. The other lengthy instrumental is effectively a drum and guitar battle between Barlow and Barre, which if nothing else, let the two of them temporarily occupy the spotlight while Anderson no doubt popped off stage for a cigarette and a lowenbrau.

A third instrumental “Quatrain” opens up the encore, once again allowing barre to show off his guitar-slinging credentials, before Tull rips into a gloriously heavy and grimy sounding “Aqualung”. One of the few Tull songs that even a none fan can name, a lesser song than “Aqualung” could have become something of an albatross around the collective necks of the band, however as the band plays it as if their very existence depended on it, that’s certainly not the case here, leaving you to wonder why more hard rock tunes can’t be this life-affirming and (once again) why Martin Barre only ever gets his dues when you ask other guitar players. The only way to top “Aqualung” is to head for the only other Tull rocker that can match it for ferocity. Fronted by a beautiful piano introduction by John Evans, which eventually morphs into a duet with Barre’s guitar, “Locomotive Breath” crashes headlong through your speakers, with the band rocking out with joyous abandon and Anderson in particular sounding like he’s having the time of his life. A closing tumble through “The Dam-Busters March” allows each member of the band to underline what they had brought to the stage that evening, before Anderson marshalls them all back to the closing line of “Aqualung”, leaving a roaring crowd and the listener at home wanting more.

For the newcomer to Tull, Bursting Out could very well be the ideal starting point – it’s certainly far superior than any other live album released by anyone that could consider them their peers. It’s a well executed exercise in how to give a rock performance, mixing just enough grit and polish, light and shade, and yes, even nailing the extended instrumental sections. Some down the years have questioned just how good a rock band Jethro Tull were. Bursting Out is all the evidence needed to demonstrate just how underestimated they were.

No Comment