Hip hop owes a debt to reggae although it’s one that is not always appreciated or acknowledged. Jamaican foundation DJs of the early 1970s, like U Roy and Big Youth, chanted over riddims that were usually instrumental versions of popular songs in Jamaica and individual sound systems battled to rule the dancehalls. Fast forward to the 1980s in Bronx, New York, and like minded DJs like Kool Herc were spinning instrumental tunes at street fairs and house parties where fledgling, proto-rappers hyped the music and the crowd and then began to rhyme over the beats.

U Roy and Big Youth remain active today and they can still drop some knowledge on the youngsters coming up. Listen to the two men verbally spar on “Battle of the Giants” from Youth’s 2000 retrospective Natty Universal Dread or more recently, on the Red Stripes’ 2015 single “I Wonder Why.” The men, both past retirement age, still have the chops to carry a song.

Despite hip hop’s reggae roots, collaborations are not as frequent as one might think. One off reggae and hip hop partnerships do occur, but the quality can vary. In 1994, Biggie and Diana King set the bar pretty high with “Respect,” a cut off of Ready to Die, the Brooklyn MC’s debut album. The Fugees did right by Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry” and, early on, rap DJs and producers poached samples from reggae artists and reggae remixes of rap songs have spawned a small industry. Hip hop artists with Caribbean roots, like KRS-One and Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, of A Tribe Called Quest, sprinkled those influences into the mix and Damian Marley and Nas partnered up for the long player Distant Relatives, a rare, full length collaboration, in 2010.

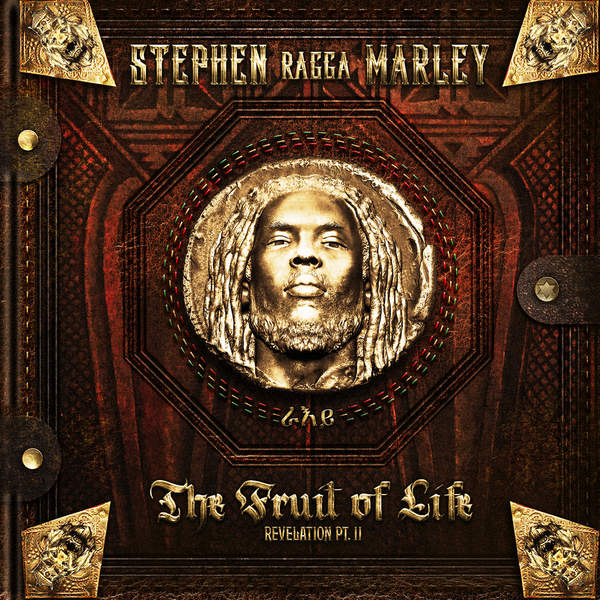

Stephen Marley’s new album, Revelation Pt. II: The Fruit of Life, is his fourth proper LP and hip hop is clearly on his mind. Revelation, Pt. II, follows Revelation, Pt. I: The Root of Life by five years and while the albums have similar titles, they are conceptually different. Revelation, Pt. I was more roots reggae, with a slimmer guest list. Revelation, Pt. II, amalgamates reggae, electronics, rap and rhythm and blues for a global sound that in many ways reflects the world we live in, where culture seeps across borders, real and virtual. Marley also assembles the A Team for this release, or maybe the A- Team, depending on your point of view, with many guest stars, mostly from the world of hip hop. Oh, yes, and Iggy Azalea (!), Pitbull and Twista. (The B Team?) More about Iggy later. Brothers Junior Gong and Ky-Mani are along for the ride, as is son Joseph, and father Bob’s voice is there too, the emotional impact of which cannot be overstated.

Marley, who produced the album, is a skilled knob twiddler and the record sounds good, loud. Keyboards wash over lush landscapes of sound. Bass guitars pop and thrump. Hip hop beats punctuate some musical passages and horn sections ring out, adding fullness to the music. Electronics gurgle and chirp. Beat boxes and drum kits peacefully coexist, adding to the richness of the listening experience.

Marley has a vision and the album is ambitious, embracing a diversity and range outside of reggae. Sometimes, when artists are described as ambitious, it’s meant as a dig and it implies overreaching or stretching in ways beyond the artist’s talents. Here, the description is not meant as a slight; Marley is talented and if anything, the modesty with which he approaches his talent can undermine the power of his vision, especially when he delegates to the less talented of his guests. Some of the songs suffer from the too many cooks rule, as if the head chef promoted democracy in the kitchen over the taste of the food. Somebody or something is going to get burned.

The elephant in the room, of course, is Marley’s father. Has any article written about him (or his equally talented brother Damian) failed to mention Bob, one of the most successful and revered musicians of all time? (An informal search suggests, maybe.) Like a lot of things in life, this must be both a blessing and a curse. There is a familiarity in Stephen’s voice; when you hear it, there is almost always a moment of, is it or isn’t it. His voice does resemble his father’s but it is distinguished by its own pleasant layer of grit and, sometimes, it bears a weary ache that can add emotional heft to his more serious songs. Marley, at 44, is already eight years older than his father was when he died and his voice has aged well.

The deeper problem may lie in the expectations we place on any musician with the last name of Marley. Or, maybe, Marley feels burdened by the expectations he places on himself, as his father’s son. “Father of the Man,” the album’s eleventh track, seems, at least initially, to address this. A sample from Nina Simone’s “Keeper of the Flame” floats in and out of the mix, to which Marley has added this refrain: “nobody knows the pain” and “everybody knows his name.” Then, “if you come from the rock, don’t run from the rock, keep your conscience clean and put the weight on your back…a foolish builder leaves out the corner stone…my destiny is in my own hands because the child is the father of the man.” Before he can air some of this out, Marley cedes the floor to Wyclef Jean, a frequently awkward rapper, who free associates about 9/11, the death of Martin Luther King, John Kennedy and his own aborted run for the presidency of Haiti.

This is not the only track where Marley moves out of the spotlight in deference to his guests and sometimes that decision elevates style over substance. “Tonight (It’s a Party),” a generic club banger, features DJ Khaled, an enthusiastic shouter and the Samuel L. Jackson of popular music, Wacka Flocka Flame, (his second appearance on the album), and the aforementioned Iggy Azalea. Iggy has fallen on hard (musical) times and her appearance here probably won’t revitalize her career. (Did she really just rhyme cities with titties?!) Some of her people should probably tell her affecting a Jamaican patois will not vault her back onto the Billboard Top 100. (Although, on second thought…)

In other places, the guests feel (mostly) right. “Babylon” kicks off the record with an indictment of the injustices that pervade many parts of the world today and it’s impossible to listen to the song and not think of the Black Lives Matter Movement in the United States. Just to emphasize the point, Stic.man and M-1, of hip hop’s Dead Prez, career agitators, contribute typically hard-hitting verses that bring home the evils of Babylon. Junior Reid is there too, and adds some words of his own, but he lacks his usual energy and his trademark warble smolders rather than burns.

“So Unjust” begins with a verse from Rakim (where you been?) who would sound good spitting the New York City Yellow Pages and also features the underrated Canadian MC Kardinal Offishall, whose own music has long referenced reggae. Rick Ross, a capable rapper when he’s awake, (and don’t assume that because he has a mike in his face that he is), drops some tight first couplets on “The Lion Roars,” but he then disappears and the song morphs from hood tale to something completely different. Busta Rhymes, along with Jamaican dancehall star Konshens, joins the party on “Pleasure or Pain,” but that cut, along with “Thorn or Rose,” (Black Thought, what were you thinking?) fails to rise above the treacle.

Most of the album’s songs can be sorted out along clear lines; some tracks have a more roots reggae feel, with poppy overtones, while others reflect a hip hop sensibility, befitting the guests. Several tunes fall comfortably into R & B. Then, there are those songs that can be best categorized as a kind of hybrid reggae, baby-making music that Marley and his brothers have sometimes engaged in, with varying degrees of success. (Seduction, like comedy, is a challenge best left to the experts. Shout outs to you, Maxwell and D’Angelo.)

“Music is Alive,” featuring Painkiller and brother Damian, is perhaps the most joyful cut on the record. The song is upbeat and it sounds as though Marley has spent some time locked in a room, listening to Kris Kross and House of Pain or maybe the entire Tommy Boy catalogue. This is not a bad thing and the shout out chorus and rapport between Stephen and Damian add to the exuberance of the cut. (Check out “The Traffic Jam” from Marley’s 2007 album, Mind Control, a humorous take on a traffic stop that shows the brothers in fine form.) “So Strong” is another standout track and when Shaggy “Mr. Boombastic’s” deep, distinctive rumble kicks in it adds unexpected color and flavor to a backing track that evokes the Stax Records sound. Bounty Killer brings it on in the sufferer’s tale, “Ghetto Boy.” The Killer’s voice, always commanding, can shift to menace on a dime. The interplay between the sneer in his exhortations, and the voices of Marley and Cobra, another basso profundo ragga veteran, suits the subject matter well. “Rock Stone,” the album’s most straight-up reggae tune, with some dub step flourishes, is also a highlight and features dancehall stalwarts Capleton and Sizzla.

Marley book ends the record with The Great Dictator’s Speech, from the Charlie Chaplin film, The Great Dictator. The opening track is an excerpt and the final proper cut on the album contains the entire speech, with strings swelling in the background. It is impossible to know if something specific motivated him to include this broadside against authoritarian rule and plea for humanity. Prescient? Maybe. But the words offer a powerful reproach to some of the political winds currently swirling around the United States and Europe and are consistent with Marley’s own world view:

Then – in the name of democracy – let us use that power – let us all unite. Let us fight for a new world – a decent world that will give men a chance to work – that will give youth a future and old age a security. By the promise of these things, brutes have risen to power. But they lie! They do not fulfil that promise. They never will!

Only Jah knows.

No Comment