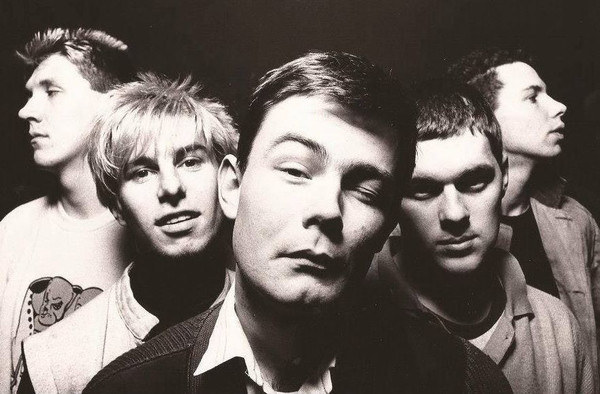

THE WOLFHOUNDS formed in Romford, Essex in 1984, plying their trade in the local Rezz Club before playing gigs further afield, notably at The Clarendon in West London.

Debut single “Cut The Cake” arrived in February 1986, gaining single of the week status in all three of the main music papers. Sadly, early critical success didn’t translate into sales: an all too familiar situation for bands of the era. They also contributed a song to the hugely influential NME ‘C86’ compilation tape, which raised their profile somewhat (in fact that’s where I first heard them). The classic second single “The Anti Midas Touch” came next and remains their best-known song.

Two more singles arrived in 1987 along with the debut album, Unseen Ripples From A Pebble. It picked up more good reviews but the band’s profile stayed at about the same level. Following another couple of singles in 1988, the band returned in 1989 with a re-energised sound. Unseen Ripples... had been a great debut, but it did suffer from a fairly thin production. However Bright and Guilty introduced more aggressive guitar tones, a punchy rhythm section and Dave Callahan’s vocals spat even more vitriol than on previous releases.

1989 proved to be a fruitful year and the strength of the material was astonishing. Bright and Guilty would have been a strong statement for any band but to then follow it up with another incredible album, Blown Away, just a few months later really emphasises how they were firing on all cylinders.

To discuss these two albums we spoke to Dave Callahan to shed more light on this time:

BM: Your early recordings share similarities with artists such as The Fall, Wire, Pere Ubu and Captain Beefheart, amongst others. All have a somewhat awkward and unique sound. Were these bands influential and who else did you find inspiring?

Dave Callahan: Yeah, I loved most of the post-punk bands and saw many of them live. My 7” collection is full of photocopied sleeves and hand-stamped labels. A friend once described us as looking like “ex-mods that have discovered Wire” but, in fact, it was more ex-post-punk fans that discovered sixties garage – though it wasn’t too far off the mark! But, really, we listened to most genres and still do. I have a particular liking for the funkier African music from the 60s and 70s these days, but I listen to hiphop, reggae, northern soul, rockabilly, folk, electronics – anything as long as it’s pretty raw.

I fell in love with Beefheart after hearing “Sheriff of Hong Kong” on John Peel – it was a whole new way of hearing music, and definitely informed our main idea that we could make pop music with a whole lot of discordancy in it – an idea which abides to this day.

You began on the excellent Pink Label alongside great bands like The June Brides, That Petrol Emotion and probably most importantly, McCarthy. Was there a feeling of kinship amongst these groups?

Well, none of us knew each other before the label and we all got on – some of us still know each other now (particularly with the easy access provided by the internet). We got on particularly well with McCarthy and used to tour together and co-headline gigs; we even rehearsed at East Ham Football Club for a while, though poor Tim had to sit through it all to make sure we didn’t raid the bar when no one was looking.

We pretty much took the first record deal we were offered – famously, after Simon from the label rang my mum’s at 2am and I said ‘yes’ to finish the phone call quickly. The best recording we did for the label was the first EP, particularly the songs “L.A. Juice” and “Another Hazy Day On The Lazy ‘A’”, which preserved our live sound pretty much in amber. In the studio, we should have carried on bashing them out live with limited overdubs for a while but, unfortunately, but got blinded by the potential of the studio without understanding how to use it well. “The Anti-Midas Touch” is one of our best songs and doesn’t sound bad recorded, just a little tinny, but live it was much more like The Saints or something (or even Nirvana – insert ironic emoji).

The release of The Essential Wolfhounds compilation in 1988 seemed to draw a line under those early years. Did it feel that way for you at the time ?

Very much so. By then, we saw no affiliation with almost all UK indie bands (even the ones we liked) and that LP was a way, in retrospect, of freeing ourselves from the shackles of jangledom. We were listening much more to US post-hardcore bands, hiphop and even Slayer, and saw ourselves as musically closer to MBV or Fugazi, but with a much different worldview and edge, lyrically.

You recorded three Peel Sessions, later released on the 2018 compilation Hands In The Till. Any specific memories about recording those ?

The overarching memory is how run-of-the-mill the process seemed. You wheeled your gear in on time, bashed most of it out live, did a few overdubs, went to the pub while the bloke from Mott the Hoople set up a rough mix and returned for the fine-tuning.

I did five sessions between 1986 and 1999, and they were always the same. It was a good way of working, as the results show.

My only strong memory is a bit cringeworthy: we had a new song called “The William Randolph Hearse” for the last session – it’s good, but it was out of my very limited vocal range and we had to slow the tape down for me to sing it, which is embarrassingly apparent to the trained ear. Naively, it never occurred to us to change the key by using capos! I sing much better now, a fact I put down to finally giving up smoking in 2007.

The Wolfhounds and McCarthy both taught me a lot about politics. Whilst McCarthy had a direct political message yours was a little more abstract maybe?

The songs on Bright and Guilty spoke volumes about living in Thatcher’s Britain and paint a vivid picture of life on the dole or in low-skilled jobs. I presume you were documenting and observing scenes from your everyday lives?

I doubt we taught you much about politics, but McCarthy were probably eye-opening, being all educated and that.

My political opinions are pretty simple and remain the same: we’re in one of the world’s richest countries (fifth to seventh, depending on which journalist is making up the facts) and there’s no excuse for anyone to starve or not get a decent start in life, no matter who or what they are. Everything comes from that, though I’m not sure that any particular creed other than socialism comes anywhere near bringing that ideal to fruition. However, I’m always sceptical and mistrustful of individual motives.

But, otherwise, the words came from straightforward observation – any depth, nuance or interest is all in the editing process.

Many of your songs highlight issues like pollution, corruption, poverty, the housing crisis and consumerism. I presume you find it depressing that the issues you were singing about 31 years ago are still very much a problem today?

Well, I didn’t expect to change anything, but it would have been nice if those in charge had tried a bit harder, wouldn’t it? I have some faith in local activism and the many selfless people working in their communities and in some unions, but otherwise the Tories will always look after their own by bribing the bourgeoisie and Labour has largely become the bourgeoisie. I had high hopes for Corbyn’s manifesto, which was ideal, but he gave too many concessions to his numerous self-interested enemies for it to ever get through, in retrospect. Some kind of green industrial revolution is urgently needed for the environment and jobs, but even the Green Party seem to have lost sight of that.

The song “Ropeswing” really captures the transition from childhood to adolescence, perfectly describing those sun-baked days of the mid 70s. There’s a palpable sense of nostalgia in the song which I presume was autobiographical?

Yes, I love that song, which was one of the first we ever wrote as a band (and one of the best lyrics I’ve written). It was mostly me and Clarkie in his mum’s council flat and we dropped it for ages until we had to do the ‘difficult second album’. The music is kind of a lift from “Candy Skin” by the Fire Engines, but slowed down. Andy added some out-of-tune banjo and pretty much made the song in the studio.

The lyrics are absolutely literal and describe a kids’ rope swing over the River Ingrebourne in Harold Wood Park in Essex. We used to use it during lunchbreak and after hours when I was in my last year of primary school. There was a dead branch on the tree’s trunk known as ‘the hook’ and you would hitch the rope over it. The rope would jerk and pull off the hook as you reached the apex of your swing and throw you in the river. I got quite good at staying on – but not until after I’d ruined a few sets of school clothes.

Was there an American influence at this point? I certainly hear elements of Sonic Youth, especially on Blown Away (the title track, “Tropic Of Cancer”, “Skyscrapers” and “Rite Of Passage”). The Bright and Guilty song “Ex Cable Street” always reminds me of early R.E.M. as well.

Well, we were listening to a lot of that kind of stuff at the time, along with things like Big Black, Dinosaur Jr, Pixies and Throwing Muses – it was more interesting than most UK stuff and bound to rub off. We had already played around with unusual tunings (e.g. on “Handy Howard”), so those bands in a way opened the door to the wider possibilities. But, as with all ‘influences’, they either lent themselves to our creative will or they were discarded.

You toured with My Bloody Valentine on their Isn’t Anything tour. Were they also an influence on the toughening up of the guitars on Blown Away?

Yes – we’d always got on with the band since they supported us early on in Hackney in 1984 and it was exciting to see how they’d twisted their fuzzy indie-pop sound into something much more robust. The tour was a lot of fun and we still have a good time on the very rare occasions we bump into each other these days. They led by example and were an encouragement, you might say.

However, we inadvertently wrote ourselves out of any revisionary elevation by keeping a socially aware edge, while most wanted to escape into the noise at the time. I viewed volume and noise as awareness heightening phenomena rather than an aid to getting stoned – I reckon I’m still in the minority there.

Andy Golding’s guitar playing is stunning. One of the unsung greats of the indie scene for sure. Bright and Guilty had plenty of gnarly guitar parts, but by Blown Away there’s an even bigger maelstrom of noise.

It seems quite a leap in just a few short months. What do you recall about the sound developing?

Yeah, he’s great – he’s always rated by people when they hear him. Blown Away is basically a conversation between my guitar and his. Whenever he does lead, I fly off somewhere else, and vice versa. That remains to this day. You could say we kind of aim for Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd, but we both want to be Tom Verlaine.

We had been very disappointed by the lack of attention gained by Bright and Guilty, which we’d recorded in a big plush studio with the Buzzcocks’ engineer, and finally got near the quality and sound we wanted. It then sold far less than Unseen Ripples… , which is still our least favourite record (sorry, indie-poppers!). However, this meant we had nothing to lose by getting more extreme.

A bass player and guitarist had left in quick succession and we were in limbo for a while, so I started writing a prospective solo LP in a shared house in Forest Gate. Somehow, Andy and Frank got to hear some of the songs and were excited enough to want to work on them (I still have the cassette with the roughs). We soundproofed a rented basement in our manager’s house in East Ham and rehearsed at top volume, experimenting with our instruments and sounds, and roping in Mary Hansen (later of Stereolab), who was sleeping on the kitchen floor at the time.

It was a recipe for creative success and commercial disaster, of which I’m still very proud. We recorded it in Berry Street Studios in Farringdon (where I was starstruck by its history: Raincoats! This Heat! The Slits!) with a youngish Ian Caple, who remains a great producer to this day (Tricky, Tindersticks, etc). We got to experiment in a basic way with an Akai sampler in the studio, which sowed the seeds in my head for Moonshake. Despite the sleeve listing Alan Stirner, he doesn’t play a note on Blown Away – the guitars are all me and Andy.

The only person in the press who really ‘got’ the LP was Bob Stanley in the NME, for which I’m eternally grateful.

There are lots of atmospheric samples and effects on Blown Away, like the intro to “Rite Of Passage”, where we hear a wasted Joey Ramone rambling away ( I’m going to confess that for at least a decade I thought it might have been Sylvester Stallone! ) and the “You killed him in your goddam Brooks Brothers suit…!” clip which I presume is from an old gangster film? Also the song “Personal” has dub and jazz elements.

Did these experiments start the interest in sampling which you later developed for your post Wolfhounds band Moonshake?

The shouty poet is Lawrence Ferlinghetti, I think – but, yes, the potential for sampling was first noted there and in the sessions for the B-sides of “Son Of Nothing”, which stole snippets of Jimmy Lee Swaggart recorded ‘confessing’ off the radio for the instrumental, “Cottonmouth”. Moonshake was originally meant to sound like the harmonies of The Byrds over Metal Box with added twisted samples, which still sounds like a magnificent concept to me!

Mary donated the edited tape of Joey Ramone for Blown Away, but I’ve no idea where she got it from.

The artwork for both these albums is great. Bright and Guilty has the densely packed collage/painting, which I spent ages deciphering; and I’ve often wondered why a map of Antarctica was chosen for Blown Away? Any stories to tell about the sleeve designs?

It’ll seem super-prosaic, but the Blown Away map was simply chosen because a child’s atlas happened to be sitting around while we racked out befuddled brains for ideas. The same thing happened with Eva Luna: there was a copy of Isabell Allende’s book on Moonshake’s drummer’s bookshelf while we sat around coming up with crappy ideas (I still haven’t finished it).

The Bright and Guilty sleeve was largely compiled by Matt Deighton (of Mother Earth, our guitarist at the time), Frank and Andy using scissors, Pritt Stick, poster paints and a sheet of my lyrics (these were deemed “surprisingly good” by Frank, after the Unseen Ripples ones were rather shit, overall). Incidentally, we’ve retained our graphics guy, Andy Royston, to this day – he’s amazing.

The Wolfhounds first phase came to an end in 1990, following one more brilliantly intense album, Attitude. What were the main reasons for the split?

Again, really prosaic reasons: we had no label, no money, no prospects and were still rehearsing through practice amps in bedrooms – we wanted much more.

Homestead Records in the US seemed interested for a while (that would have been great) and Creation were keen after Blown Away, but didn’t like Attitude so much. We just kind of fell apart, but signed to Creation anyway – me with Moonshake and Andy and Frank with Crawl.

Creation were good enough to send Wolfhounds on tour with MBV and The House of Love, the last of which looked good on paper but soon became disastrous and sealed our fate after we failed to get on with the ostentatiously public-school headliners and our van broke down, leaving us stranded on the hard shoulder and we arrived on the last date after it had finished, without bothering to tell the headliners in advance. Very unprofessional – but we were literally not professional, in any case. You have to bear in mind that we were always more Happy Mondays than New Order – chaos abounded.

I still remember the long, cold, dark journey from Norwich back to London sitting in the AA van, thinking that might well be ‘it’ (though we did manage a few more dates of our own).

Your presence on the C86 compilation means you’re often tied to that particular scene. “C86” is used now as a shorthand for “twee” indiepop bands.

The Wolfhounds are certainly not that and considering that at least half the tape was full of spiky, angular, noisy sounding bands such as Big Flame, The Mackenzies, Age Of Chance, Bogshed etc it seems odd that it’s now associated with fey anorak pop!? What are your thoughts about your links to ‘C86’ as a scene?

It’s become fashionable to deny there was a scene but there actually kind of was at the time, in the sense that many of the bands on the tape would share gigs and sleep on each others’ floors. But those same gigs would also feature the likes of Sonic Youth (when they were over), Band of Holy Joy, Membranes, etc.

The tape – meant merely to be a snapshot of indie bands in that month – had the unfortunate effect of excluding a wider range of music, but the semi-fortunate effect of giving us a leg-up that we weren’t ready for. If I have one regret it’s not putting “The Anti-Midas Touch” on it instead of dismissing the opportunity with an old and inferior song. Primal Scream certainly had more of the right idea – and it paid off for them.

Your vocals suggest to me an almost permanent state of frustration with the world around you! I recall thinking of you as the only singer who sounds even more pissed off than Mark E. Smith! (that’s a compliment by the way!)

However, does your interest in birdwatching and writing articles on the subject plus your recent more ‘folky’ sounding solo single suggests a more sedate side?

The only similarity between me and MES is that we’re misunderstood this way and are/were rather jolly fellows in person. And the reluctance to stick to one subject in a song, of course.

I can assure you there’s nothing sedate about birding, which has taken me to some of the roughest parts of the globe and seen me in weirder situations than most rock bands get into – the rock’n’roll lifestyle being a massive cliché, now beloved only of mediocrities. Overall, it’s nice to be able to pay my mortgage writing about something I’m interested in.

‘There’s always been a folk element to my music’ … Actually, I view pop and rock music as monetised folk music. Simple chords, Chinese whispers and storified lyrics. Folk music evolves as it’s passed from person to person, a phenomenon characterised as ‘plagiarism’ by music lawyers, but actually essential to music’s DNA. I view sampling the same way, if it’s done creatively.

Finally, what are your personal favourites on each of these albums ?

Unseen Ripples: actually the first EP on the reissue version, but otherwise “Me” and “The Anti-Midas Touch”;

Bright and Guilty: “Non-Specific Song”, “Useless Second Cousin”, “Rope Swing”, “Charterhouse”;

Blown Away: “Rite of Passage” (but all of it, really);

Attitude: “Gutter Charity”, “Vertical Grave”, “Magic Triggers”.

Thanks for taking part Dave.

I must point out to anyone reading this article that The Wolfhounds are still very much a going concern and the albums they’ve released since reforming are just as great as their initial releases.

All the new albums can be found on their Bandcamp page (https://thewolfhounds.bandcamp.com) as well as some rare live recordings stretching back to their earliest gigs. The latest album, Electric Music, has only just been released and is highly recommended; one of those rare bands who have never let me down.

No Comment