Before “All The Young Dudes”, before Top of the Pops appearances, before David Bowie, Mott The Hoople were a brilliant live act that arguably struggled to transfer the tremendous energy that they generated on stage to the studio. It’s not that they didn’t try, indeed, they recorded four solid albums that were met with mass apathy by the record buying public, to the point where few in the pre-internet days realised that they had recorded any studio albums prior to “All the Young Dudes” being a hit.

The story so far…

Through the mid to late 60s The Doc Thomas Group / Silence had been a band of jobbing rockers led by the dual creative forces of guitarist Mick Ralphs and organ player Verden Allen. Hard working, while not exactly life changing, they struggled to get a recording contract until one day, after a third promise of a meeting had resulted in nothing, Ralphs burst into the office of Island Records employee and general misfit Guy Stevens. Rather than ask the office heavies to throw him out, Stevens applauded Ralphs’ bravura and arranged for he and his band to play for him.

On the day of the showcase, Stevens watched the band work together to get Allen’s huge organ up the flight of stairs to the playing area, and admiring their willingness to make an effort to take a chance, he signed them to Island as his pet project. There were two provisos though, he first being that they change the name of the band, and secondly, that they oust vocalist Stan Tippens. In typical humane Mott fashion the band retained Tippens as their tour manager. Extensive auditions for Tippens’ replacement did not yield anyone suitable, that was until the down on his luck 30 year old Ian Hunter tried out with his idiosyncratic cracked vocals, and recognising a similarly hard-working kindred spirit to the rest of the band, Stevens recruited him into the band on the advice that he lose weight, grow his hair out and never, ever, remove his sunglasses.

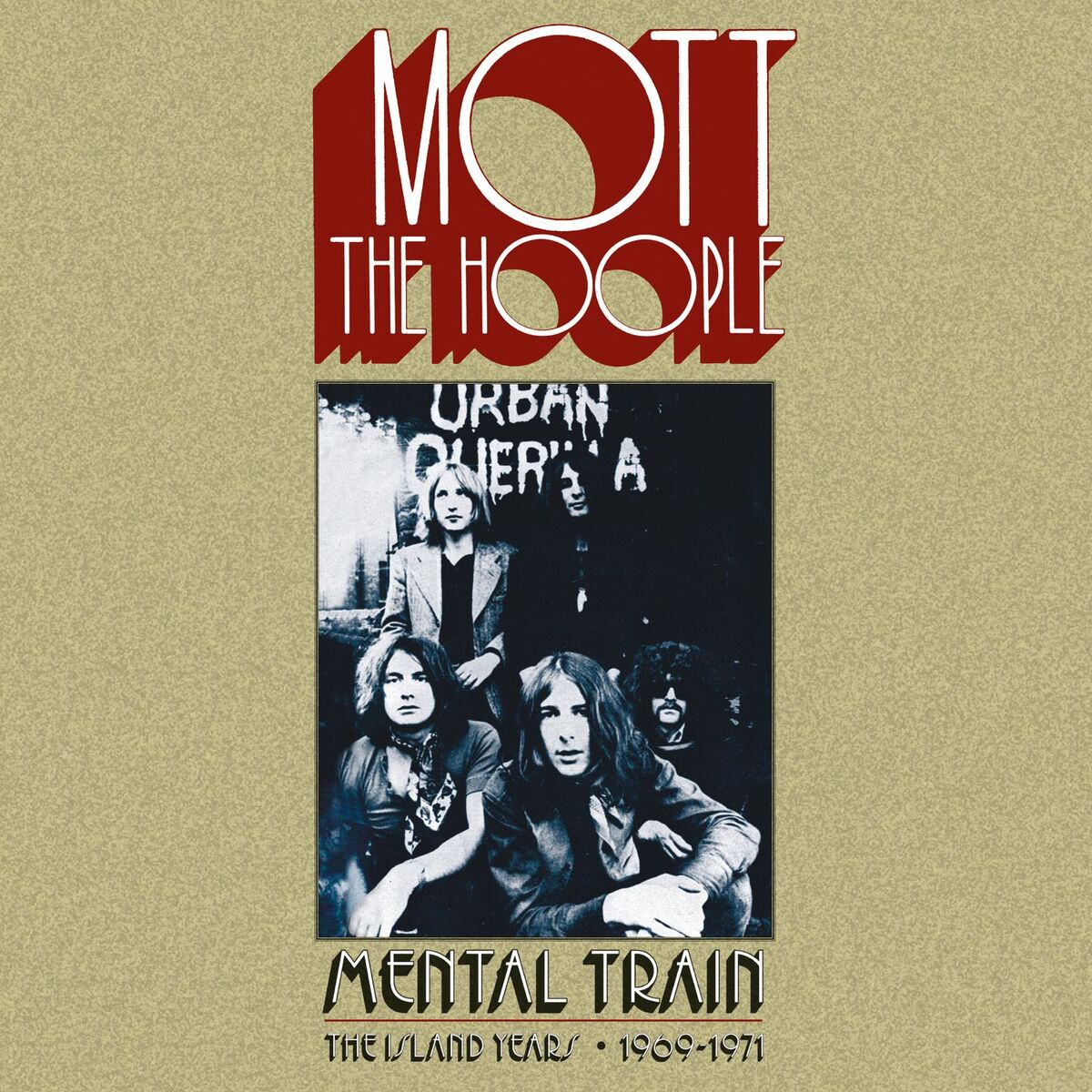

For reasons lost to the mist of time, Mott the Hoople’s quartet of Island albums have been notoriously difficult to find on CD down the years, which given the generous reissue campaigns for other acts signed to the label during the same period, and the band’s subsequent chart bothering status later in their career, is a significant oversight. Sure, there were the Angel Air reissues a few years back, but there’s certainly been nothing that you might see on the shelves of HMV. Mental Train collects Mott’s Island era albums together in one box, throws in a load of bonus tracks and unreleased extras (some at the end of the CD of the appropriate album, some on a separate disc), with a sixth disc of live recordings from the era. In addition to the actual music there are copious liner notes and an accompanying book full of photographs of the band during their time at Island.

Naturally, given that they were his pet project and none of the band were willing to rock the boat this early into their recording career, Guy Stevens’ fingerprints are all over Mott the Hoople’s self-titled debut. Obviously recorded by a band who were just grateful to have a record deal and were still bedding in their new vocalist, Mott the Hoople is the sound of five blokes searching around trying to find their musical direction, being steered by a svengali who was doing all he could to shape their raw potential into the form of what he thought a great rock and roll band should be.

With a band finding their feet and a wayward svengali / producer figure, it’s a miracle that Mott the Hoople’s debut turned out as well as it did. From the opening blast of their cover of “You Really Got Me”, it was clear that Mott already had an elemental power about them that just needed to be harnessed appropriately, however there was no such sense of control on Mott the Hoople. Much of Mott’s charm throughout their career is that, while they weren’t the top flight of naturally gifted players, it was obvious they put in a massive amount of effort to make up for the deficit. There was no harder working band than Mott the Hoople, and one of the reasons that they drew such a rabidly loyal following was that they convinced the kids that they too could be rock stars if they were prepared to put the hard graft in. Sure, sales of their albums were negligible, but they put the road-miles in and made a rare connection with their audience of kids who felt disenfranchised by their peers. It’s no accident that Mott the Hoople fans would go on to form seminal punk bands within the next decade, as everything Mott did was done with an intensity and honest hard work that inspired a special kind of devotion, regardless of the fact that their early albums failed to truly capture just what an incredible live act they were. Guy Stevens may not have given Mott the Hoople much of a sense of creative direction, but he was one of the few working the music industry smart enough to realise how special they were.

If their debut lacked cohesion due to a lack of definitive direction, then Mad Shadows at least decided that ‘vaguely unsettling’ was an interim decision on where to head, even if it wasn’t necessarily a cheery one. Not that Mad Shadows lacks subtlety, indeed there are many shades of grey featured throughout its 37 and a half minutes, with first side closer “Walkin With a Mountain” being the album’s sole upbeat number. Elsewhere, this is a tense listen, with opener “Thunderbuck Ram” showing that Mick Ralphs could deliver a dark and heavy riff with the best of them. Indeed, the song as a whole yet again underlines exactly how much Ralphs brought to the collective table in their pre-Dudes era, and just how vital he was as a creative counterweight to Ian Hunter.

Listening to Mad Shadows all these years later, you do have to worry about the state of Mott the Hoople’s collective mental health at the time. “No Wheels to Ride” is an absolute downer of a song, and album closer “When My Minds Gone” practically howls with desperation. “Walking With a Mountain” is the one moment of respite throughout the album and saves the listener from being smothered with despair, and even then it’s one of the shortest songs on Mad Shadows.

If Mad Shadows found Mott the Hoople staring into the abyss and wondering if all the hard worked been worth it, their next album, Wildlife, found them in an altogether different mood, as Mick Ralphs seized the opportunity to exert more influence over the band’s sound and creative direction for a while, with Ian Hunter seemingly preoccupied with issues outside of this music career, and Guy Stevens sidelined in favour of the band self producing the album. With Ralphs to the fore, Wildlife is a Mott the Hoople album like no other, with many tracks exploring a more laid back country-rock sound and Ralphs fulfilling a lot more lead vocal duties than he had before.

As fine an album as Wildlife is, in retrospect it does struggle to stand out among Mott the Hoople’s first four albums, simply because it’s the only one that doesn’t leap out and grab you in attempt to vie for your attention. Instead it is much more chilled out and willing to hang back, as Ralphs songs the album gave us a much more subtle version of Mott the Hoople than any other album released in their career would ever suggest. Imagine Ralph’s frustration then when time revealed that Wildlife’s best loved tracks would both be penned by Ian Hunter. “Original Mixed-Up Kid” has been resurrected as something of an anthem for fans of early Mott in subsequent decades, while Hunter’s enduring masterpiece “Waterlow” would explore a deep well of sadness on loss that only the very best songwriters are capable of peering into, never mind drink from. Perhaps even more incongruous than Hunter’s songs being the most celebrated aspects of the Mott the Hoople album that Mick Ralphs had the most influence over, is the fact that Wildlife closes with a chaotic live cover of Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Keep a Knockin’”, easily the heaviest thing on the album, and the sole track salvaged from an aborted live album.

Ultimately Wildlife had the opposite effect of what Mott were hoping for, as it confused enough fans for it to be their worst selling album to date. With a rethink obviously required, Guy Stevens returned to the producer’s chair for their next album, Brain Capers.

Of the four original albums on Mental Train, while Brain Capers shares a similar sense of coherence as Mad Shadows, but is much more of an out and out rock album, and for many fans is Mott the Hoople’s definitive release. Given the return of Guy Stevens and his distracting influence, as well as band moral being low, it’s simply astounding that Brain Capers turned out as well as it did, with its centrepiece “The Journey”, being one of Mott’s most emotive numbers. Sure, there’s still an element of silliness on the album, like calling the closing track “The Wheel of Quivering Meat Conception”, but Brain Capers as a whole ably demonstrated how much Mott had evolved and that with better luck, they could have been contenders. Of course Brain Capers bombed, selling even less copies than its three predecessors.

Now all four of Mott the Hoople’s Island albums are available again as part of Mental Train, one can only hope that they will given individual releases as well, to allow those who can’t afford the luxury of a box set the chance to discover one of the most curiously overlooked discographies of the era. While other Island acts of similar vintage (Traffic, Fairport Convention, Free, etc) have been critically acclaimed and assessed and reassessed regularly in recent decades, Mott’s Island output has remained a forgotten corner of rock music’s most fertile period, especially when you consider what they would later go on to achieve.

Outside of the original albums, Mental Train loads up each CD with a generous serving of unreleased material and demos, the vast majority of which capture the band’s kinetic energy before any production polish was added. Such is the generosity of the additional material on Mental Train, that not only is each album accompanied by contemporary additional material, but there’s a whole additional CD of extras, Ballads of Mott the Hoople, included as well. If you’re someone who prefers their Mott the Hoople to sound as wild and untamed as possible, then there’s enough material here to create a compelling alternative history of the band, just from the studio offcuts alone. Oh, and if that’s not enough, there’s an additional disc of live recordings capturing Mott the Hoople in their natural habitat.

One of the things that does leap out at you throughout Mental Train, not only on the unreleased material, but the sonically upgraded albums themselves, is the contribution of organist Verden Allen was to the early Mott the Hoople sound. Allen’s organ work was as vital an element of the early Mott sound at least as much as Mick Ralphs’ guitar and Hunter’s vocals, and in retrospect you fully understand his decision to walk away from the band when his role was diminished on their post-Island work. Not that Allen is the only beneficiary of the upgraded sound quality. The rhythm section of Pete Overend Watts and Dale Griffin propel the band forward, Ralphs’ guitar work is given a new lease of life, and Ian Hunter’s vocals sound as lived in and believable as ever. If you only have well played vinyl originals or the CD versions from the early 90s, then the sonic upgrade alone is worth the price of Mental Train, as Mott’s Island era work has never sounded better.

Looking back, perhaps Mott the Hoople were never destined to be part of rock music’s upper echelons. Instead, their appeal lays in the fact that they plugged away during the lean years, believing that they could make it through sheer hard work and immense effort. As I say, that is probably why so many influential punk icons followed Mott and that that movement adopted its ‘anyone can do it’ philosophy, resulting in a far deeper appreciation of Mott the Hoople among fellow musicians than many other big ‘name’ acts.

Mental Train is the box set that Mott the Hoople has needed for years. If you’ve always dismissed Mott the Hoople as glam rock journeymen who got lucky when David Bowie offered to pen them a hit single, then you owe it to yourself to seek out Mental Train, as it contains a whole lot more depth than many realise Mott the Hoople were capable of.

No Comment