R.A. The Rugged Man, the rap moniker and alter-ego of Long Island, New York native R.A. Thorburn, is the kind of guy who arrives early to a party, and leaves late. He drinks too much and pukes in the bathroom. When no one is looking, he jerks off in the punch and then giggles in the corner when party goers drink from the bowl. He talks about his dick. A lot. He doesn’t like people who are politically correct but he does likes hookers. Also, he wants you to know that he likes the word “hookers,” and he uses it frequently. If you do not, you should probably stop reading this now. If this is your kind of thing, and, apparently for a lot of people, this is their kind of thing, dear reader, please continue. Actually, please continue.

Okay, hold up. For the past week, I’ve been living with The Rugged Man. I dug out my CD of Die, Rugged Man, Die, from behind the couch, where it may have been since the early oughts. I searched for my copies of Soundbombing. I listened to his other albums. I listened to his guest verses. I watched interviews. I watched the video for the single from his new record. I did all these things multiple times. Now, I’m here to say that the man won me over. The pleasures of Die, Rugged Man, Die, so evident to my younger self, and the entire Rugged Man catalogue, became apparent with multiple listens and deep immersion. The man is no misogynist. He’s a satirist and an observer of the human condition. If you can’t appreciate that, then that’s on you and not The Rugged Man. And, the man regularly drops pearls of wisdom. (Example: in a lyrical high noon, Kool G Rap destroys Bob Dylan. Yup, he said that.)

The Rugged Man is a legend in rap circles. At eighteen, he signed with the renowned label Jive, an early and important proponent of rap music, then famously decided he wanted out of his contract after an employee sued him for sexual harassment. At a label showcase, he performed songs with titles such as “Cunt Renaissance” (the recorded version has an intro from Biggie Smalls) and “Every Record Label Sucks Dick,” used a duct-taped prostitute as a stage prop and insulted label mate Keith Murray and his entourage. Murray’s debut album went gold for Jive just a year earlier. Instead of cutting him loose, Jive sat on the Rugged Man, and refused to release him from his contract. He languished in a kind of artistic purgatory for years, without the ability to release a proper album, an all too common occurrence in the music industry. His debut for Jive, Night of the Bloody Apes, was never released.

Eventually, The Rugged Man signed with Nature Sounds, a proudly independent Brooklyn label, that has put out releases by luminaries like Wu-Tang member Masta Killa, Black Market Militia and Hell Razah, a Wu affiliated artist and a member of both the Sunz of Man and Black Market Militia. The label released the first Rugged Man project, Die, Rugged Man, Die, in 2004 and has been his artistic home since that time. Over the years, The Rugged Man was also featured on the Rawkus Records compilation series, called Soundbombing, which included both well-known and more obscure rap artists and producers, and was a hard-hitting and critically acclaimed show-case for those artists. (Missy Elliott was on Soundbombing III. Did you remember that? I didn’t!) The Rugged Man also recorded an album for Rawkus in 1999, called American Lowlife, but that, too, never saw the light of day.

The Rugged Man has appeared on numerous albums and in videos by other artists. In 2006, he was featured on the song “Uncommon Valor: A Vietnam Story,” the fourth track on Servants in Heaven, Kings in Hell by Jedi Mind Tricks, where he handles verse two. The song, told from the point of view of a soldier in Vietnam, has The Rugged Man assuming the role of his father, a Vietnam vet, who is shot down over Cambodia and severely injured. This verse demonstrated to many fans that The Rugged Man was capable of sophisticated rhymes about serious subjects, with writerly details. The song’s poignancy and The Rugged Man’s rapid, confident flow, garnered positive attention. The on-line publication HipHopDX called it the verse of the year. At some point, Rolling Stone magazine went as far as to call The Rugged Man “a blue-eyed Biggie Smalls,” an unfortunate comparison that may have done more harm than good, and a label that The Rugged Man himself would probably reject.

Sometimes granular details can elevate a song because there is a universality in the small parts of life with which all listeners can identify. In “Uncommon Valor,” The Rugged Man uses details from his father’s life and his own, which manage to make his guest verse an indictment of wars fought by working class men (and now women), without ever getting directly political. The song itself is really a short story, with a universal message. Or not. Many artists resist navel gazing about their work, and maybe The Rugged Man does, too.

The bigger point is that The Rugged Man can write and rap with facility and grace, and often does so better than many stars. He can be direct, or he can drop cryptic bombshells for people who dig referential lyrics, and they reveal his intimate knowledge of hip hop culture. “Uncommon Valor” is but one example of his deep, lyrical side. Unfortunately, sometimes he punches low or revels in the scatological. There is a place for the latter in all art, to challenge, to push boundaries and to stick a thumb in the eye of critics and tastemakers who function as gate keepers for what we should or shouldn’t patronize or consume. But still…

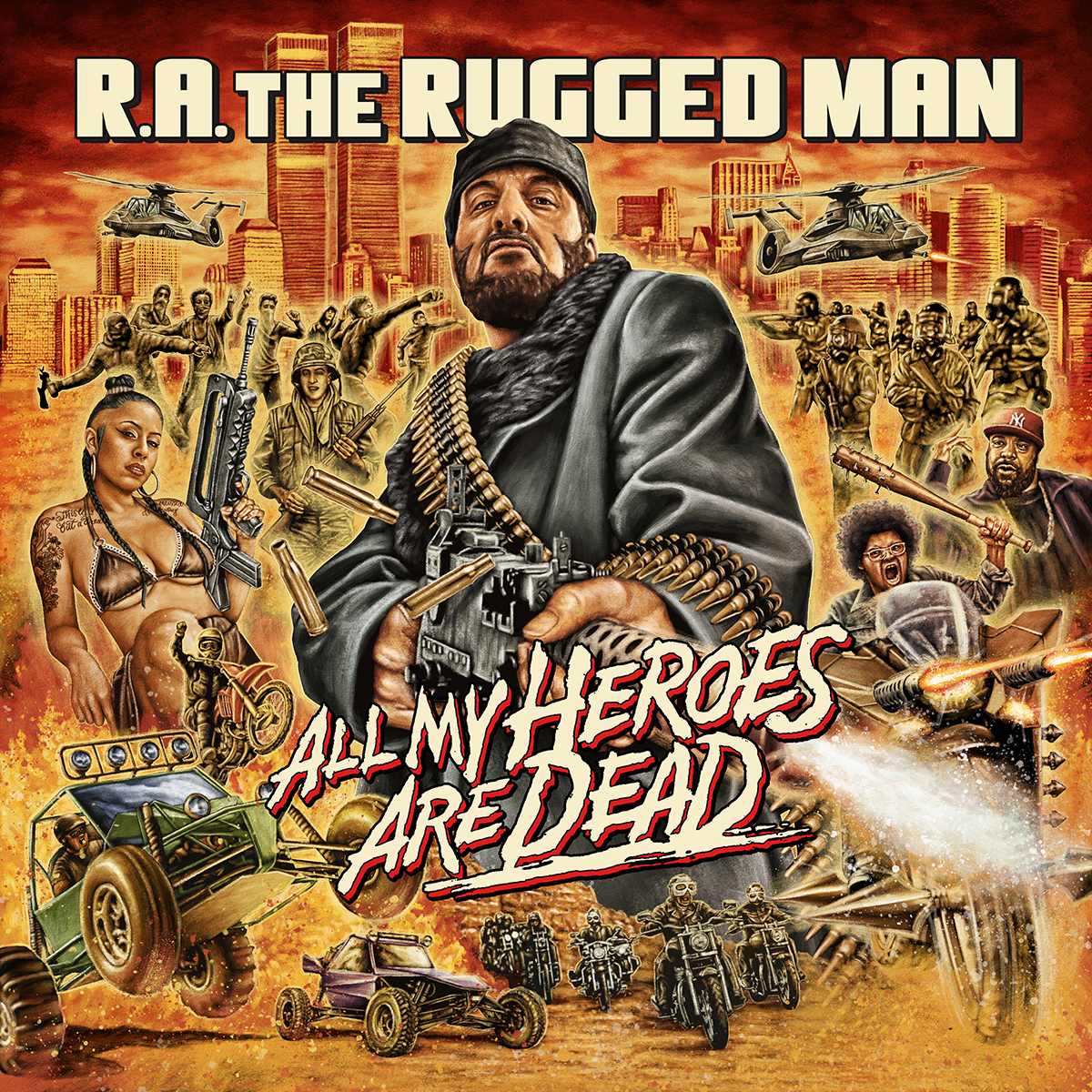

The Rugged Man recorded two subsequent albums for Nature Sounds. His last release, Legends Never Die, dropped in 2013. In addition, he has appeared in videos by other artists, become a film critic and producer, and is directing a film based on his family’s life. By all accounts, The Rugged Man is a busy man. Now comes his latest record, All My Heroes Are Dead, a twenty-two-track behemoth, spread out over three vinyl records and available in other formats as well, and it’s busy, too.

The Rugged Man, is a proud, working class rapper, who sounds like Sylvester Stallone but with better articulation. Over the years, his voice has developed a pleasant gruffness, evidence of a life lived hard. He can rhyme fast and he can rhyme slow, and he can drop gems of knowledge that will force even the most devoted fan or rap aficionado to decipher the line’s meaning, like a scholar poring over the Talmud. He’s a throwback, but in a mostly good way, with a lyricism that will satisfy old heads and the youngsters, too. The Rugged Man is a white rapper for people disinclined towards white rappers, but he’s not a teddy bear like, say Mac Miller, who The Ragged Man has said, is not quite his “genre.” (His niece loves Mac Miller.) He’s a jokester, a finger in the eye poker, who doesn’t mind taking a whack at the culture’s shibboleths. (Did he really say that Kendrick Lamar is not a top-five lyricist? Yup, he said it, in an interview a few years back, not on this album and he did say it in a kind of complementary way. Kind of, and in the context of the commercialization of hip hop. But I digress.)

For this album, The Rugged Man has brought together the usual characters. Ghostface Killah, Masta Killa, Slug of Atmosphere, Kool G Rap, Inspectah Deck and Vinnie Paz all contribute verses. (On “Dragon Fire,” a posse cut, the hook is the Wu alums chanting Wu-Tang, with an added shout out to The Juice Crew. Note to young hip hop heads – look them up.) Production is helmed by Psycho Les of The Beatnuts, The Kickdrums, Mr. Green, Prince Paul and Classified, among others. The songs swing back and forth from the irreverent to the tragic. The Rugged Man is both self-deprecating and self-aware, and presents himself as a hip-hop elder, confronted by a new world in the seven years since his last album dropped. Heroes is nostalgic but not maudlin, with a sense of humor that, on some tracks, threatens to becomes acrid. The Rugged Man stares into the abyss but generally manages to right himself before the mood curdles and he transforms himself into a cranky old man who happens to be able to spit.

The lead single, “Legendary Loser,” is a typically self-reflective song, that mocks The Rugged Man’s larger than life personality and propensity for self-sabotage, which he suggests was the price of being authentic and an underground star: I misbehaved a bit, the industry was afraid of it/I couldn’t take a shit without lawyers litigating it/(He’s a slob, he’s obnoxious, he’s a misogynist!/He hates women! This shit is toxic) yo bitch, stop it/I hope your pop get his wallet picked by a pickpocket/And ya fat mother drown in a puddle of pig vomit/All I cared about was tryna get inside vagina lips and biting tits/ I was unstable, fighting, having violent fits/A point I might of missed, more irritating than psoriasis/Is at the height of this, they tried to hire a psychiatrist/My career fell apart, taught me how to be humble/Watched a $1.8 Million dollar deal crumble.

He’s the bard of the dispossessed and the marginalized on “Wondering (How To Believe),” a song told from the vantage point of three people, including himself, who experienced trauma in their lives and the song references some of the tragedies that have marked the artist’s own life. Verse two is from the viewpoint of a rape victim, and in the third verse, a heroin addict falters on the road to sobriety. “Wondering,” which features a simple refrain sung by Canadian folkie David Myles, is The Rugged Man at his most contemplative, and he questions how people can maintain their faith or ability to believe in anything in the face of such devastating loss. When The Rugged Man reveals such intimate details about his own life it may be cathartic for him but it also reinforces his realness and authenticity to the listener. The Rugged Man may be many things, but a rapper created in a corporate test-tube to sell millions of records he is most definitely not. The Bruce Springsteen of hip hop? Or Springsteen as The Rugged Man of rock and roll? As The Rugged Man might say, fuck that, and perhaps he is right.

The court jester returns for “Hate Speech,” a celebration of truth-telling, which features the word “cunt” in the chorus, and asks this burning question about the United States: “Are we just a wet vagina hole of a country?” The Rugged Man’s answer? Why, yes, yes you are, America. To remedy this, The Rugged Man wants to feed gay friends a “Chick-Fil-A sandwich,” “fat-shame a fat kid,” and force vegans to “live off of chicken and chitlins.” He also interpolates Big L and acknowledges from the jump that he’s “a prehistoric animal” that “came out the cave white.” Fat jokes, Rugged Man? Yes, in the service of satire.

Perhaps the most overtly political song on the record is “Who Do We Trust,” which features Immortal Technique, a strident truth-teller, who pulls no punches in his indictment of the United States and its foreign policy, material he’s mined before. The Rugged Man joins in, excoriating the United States for its overseas adventures. “Golden Oldies” is a tribute to his heroes and the art of the rhyme, with shout-outs to Big Daddy Kane, whom The Rugged Man holds in high esteem (look him up, youngins’) and X-Clan (you know what to do). “Contra-Dictionary” roasts hypocrites. “The Slayers Club” is another posse cut, with a booming beat and, as usual, The Rugged Man holds his own in verses alongside Chino XL, Vinnie Paz, and Sadat X and Lord Jamar of Brand Nubian and Billy Danze and Lil’ Fame of MOP. Like the other features on the album, the guests are hip hop stalwarts, with ties to the Golden Age, a fertile period for innovative artists, supple flows and complex lyricism. The Rugged Man’s heroes are not dead, but to the music industry, maybe they are.

The album ends somberly, with “The After Life,” a tribute to lost friends and family, with swelling instrumentation, and a gentle female chorus. The Rugged Man reflects on loved ones he has lost, and identifies with others have experienced the same. He laments the turmoil in the greater world. He imagines his own after life and wonders if death brings some peace to those who have passed on. This type of track has been done before, but the imagery is vivid, and the sentiment is raw, anchored by The Rugged Man’s ability to give of himself to the listener and ride the beat. The song is a coda for the latest chapter in the artist’s musical life, one with detours and obstacles, but one in which he emerges, ultimately, intact, to fight another day.

All My Heroes Are Dead could have benefited from some editing, but as The Rugged Man might say, those who can’t do, teach and those who can’t teach become music critics, so fuck off. Amen to that, Rugged Man. Amen.

No Comment