Since being the original form of recorded music, the live album continues to evolve. From the legendary live soul albums of the 60s, to the iconic double live albums released by innumerable rock bands during the 70s, then on to landmark live recordings in the 80s, and finding a new lease of life via MTV’s unplugged during the first half of the 90s.

Since the turn of the century, live albums have seen their place in our music collections threatened by live performance DVDs, and they’re often now tacked onto albums we already own by way of a ‘limited edition bonus disc’ of material. In parallel to this has been a greater focus on live recordings from the archives of veteran rock bands. Arguably, no band have taken greater advantage of this than Deep Purple, who to date have released no fewer than 47 live albums, well over half of which have been archive recordingss.

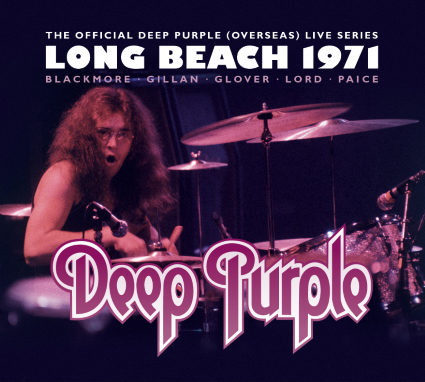

The latest in a seemingly endless campaign to purge the vaults of Deep Purple recordings of various vintage, Long Beach 1971 is released on 26 May, having been broadcast on local radio shortly after the performance. Performed by the beloved Mk2 line up of the band, it found the band very much in the ascent, having released their breakthrough album, In Rock, the previous year and making serious inroads into the American market, having enjoyed a huge hit single with “Black Night” in the UK.

The gig itself was in support of The Faces, with Deep Purple performing a generous hour long support set. With an hour to make as big an impact as possible, Purple played to their strengths, and contrasted the headliner’s rambunctious rock and roll with a quartet of hard rock epics, two of which, opener “Speed King” and “Child in Time” from In Rock, “Strange Kind of Woman” would become a standalone single in the forthcoming months and “Mandrake Root” dated from all the way back from their Mk1 debut album. Needless to say, with four songs played in an hour, the emphasis throughout this performance is based on the musical interplay of the band, though when Ian Gillan takes centre stage, his vocals are bumped up so high in the mix that it gives away the fact that this gig was originally recorded for radio broadcast. This is a minor quibble though, as Gillan’s vocal prowess and unearthly scream are a big part of what differentiated between the output of Deep Purple Mk1 and the considerably more dynamic Deep Purple Mk2, and he’s on fine form throughout this performance.

As previously mentioned, much of Deep Purple’s reputation lays at the level of musical interplay between the band. Both guitar-wrangler Ritchie Blackmore (a man for whom the repeated riff didn’t so much become a signature, but an entire artform) and organ player Jon Lord (a man who has influenced pretty much everyone who has touched a hammond organ since) are spoken in hushed tones by those for whom 70s rock music has a special place in their hearts. Mk2 also boasted the presence of Roger Glover, a bass player who would become on of heavy rock’s key producers as the 70s progressed, as well as drummer Ian Paice, the only member of Deep Purple to have featured in every incarnation of the band. Paice particularly makes his presence known throughout this performance, cementing his reputation as one of hard rock’s premier drummers, and proving beyond a doubt that he could combine the tub-thumping power of the likes of John Bonham and Keith Moon, with finesse on a par with Neil Peart and Barriemore Barlow.

Inevitably how much you’ll get out of Long Beach 1971 will be dependent on if you’re a fan of the type of extended instrumental workouts that were fashionable during the early 70s. Simply put, if you like your rock songs to err on the economical side, then you really should look elsewhere, however, if you’re a committed Deep Purple fan, then chances are that you’ll love the sound of Deep Purple Mk2 stretching their legs as they ascended towards hard rock megastardom.

No Comment