The Breakdown

THE FRENCH composer and multi-instrumentalist Christine Ott can never be accused of running with the pack in her compositional aesthetic; down the years since her first release Solitude Nomade in 2009 she’s really pushed the possibilities of modern composition, not in experimenting for the sake of it, but in trying to express and elicit a deep emotional response to her creations.

She’s returning to Manchester’s Gizeh Records for her fourth album for that imprint, Time to Die, the sequel to the highly regarded 2016 album Only Silence Remains; since when she’s worked alongside Tindersticks, composed soundtracks, released the haunting pastoralism of Volutes with her side-project trio Snowdrops (which we fell hard for and reviewed here).

A pianist, harpist, vibraphone player and percussionist of the absolute top stripe, one thing which really sets Christine apart is her position as one of the world’s few and leading players of that most recherché of early electronic instruments, the ondes Martenot. What’s that? You may well ask: for an underrated instrument it certainly is.

To précis: the ondes Martenot was patented by Maurice Martenot in 1928, the same year as the theremin was patented in Russia. Maurice had been a radio operator in the First World War, and had become enamoured with the musicality generated by radio tones; he sought to bring those tones to a controllable device.

Broadly similar in action to a theremin, the user wears a metal ring, which is then slid along a wire to create tones; later examples brought keyboard for user simplicity. Being built to order, they weren’t the sort of instrument you could pick up to have a crack at.

Her aptitude with the sweet and singing tones of this instrument necessarily means she’s performed with numerous orchestras the repertory of Olivier Messiaen, Arthur Honegger or Edgard Varèse, composers who wrote often for the instrument. She was part of Yann Tiersen’s ensemble for ten years, and has worked with Syd Matters and Radiohead. Quite the CV.

Her aesthetic: to elucidate strong sensations, powerfully evoked, calling on her skills with whatever instrumentation deemed necessary; as well as those mentioned above, on Time To Die she also plays the Roland Jupiter8 and Korg Monotrons synthesisers; timpani and tubular bells; sings. All of which talent is entirely in the service of the music she makes, which seems to come from deep and otherly places.

Time To Die is conceived as a musical fresco in eight chapters, a sensory journey between the world of the living and the dead, for which Christine weaves the deepest journey. Dive in with me, expect to be fascinated and enthralled.

We begin with “Time To Die”, which swirls up darkly like thunderheads from a cauldron of synth fuzz and thrum; distorting, rich in bass and joined in shrill, generative fury by other tones. It’s like the darker moments of Lucifer’s Black Mass, the 1971 album from Moog pioneer Mort Garson, lent modern power and extra malevolence. It takes off, hits cruising altitude flickering through dark cloud and then suddenly there’s a human voice: it’s Rutger Hauer’s swansong soliloquy from Blade Runner, here intoned by Casey Brown. Time to die, indeed. The musical backdrop shifts to include a more cohered, cleaner drone power, the dark conceit of timpani beating in your blackened chest. You’re rapt. It ends, as it has to, in thunder. We’ve embedded this one for you, and it can be found down by the sales kickers; go delight.

Perhaps the only way you can go from such intensity is to pull back, allow space and melody in which to (partially) recover; which Christine graciously allows with “Brumes”, a study in piano. The title translates as ‘fog’ or ‘mist’, to set the titular tone; and she sets about evoking that in glissando and gleam. You can feel the droplets on your skin, sense the greyer occlusion of atmospherics in the steelier bass passages; are swirled into its creeping fronds. Nearly seven minutes of solo piano delight.

“Landscape” cleaves to the same pastoralist evocation, a simple motif ringing with paused nuance, Christine’s voice high and otherworldly in the vein of Morricone collaborator Edda Del’Orso. She’s multitracked, has a mastery of the high register, and urges the tune ever on as it begins to canter, clear as a spring dawn. It concedes to “Chasing Harp”, in which she takes a solo turn on that instrument, ethereal and fluid, warmed by reverb, almost shoegaze in tone, glorious resonances and overtones singing out in a beautiful space, all distance, almost eavesdropped.

Moving away now from the verdancy of that trio of tracks, “Horizons Fauves” is a more solemn mood, prepared piano stern with the rushing hiss of synth, darker electronic undertows never quite giving way, a signifier like a column of smoke on the horizon; there’s something darker nearby. Christine initially works within, then breaks free of this atmosphere with a rippling masterclass in solo piano, light and shadow at play, low sun through trees.

“Comma Opening” sees her at that magical, otherly ondes Martenot, for a delicate tone poem, coaxing it into ever more beautiful drone. Stars of the Lid would have made a masterful collaboration with her on this high form (perhaps A Winged Victory For The Sullen should work with her? – it’d be beautiful); it’s an absolute highlight, avant-garde ambience that’s pure like dawn. It’s joined in its solo song by a background shimmer, the better to sing even higher, clearer; Snowdrops collaborator Matthieu Gabry was, I was guessing, at the mellotron, faux-string melodies in the gentlest consort; but the polyphony, I’ve reliably informed, is a product instead of the mastery of the instrument. This track, so far away from the darkness of the opener, is Edenic and transcendental. Bang on.

“Miroirs” is a fluid modern compositional piano outing, a companion piece to “Brumes” in melodic runs that demands your immersion; and we have only “Pluie” to warm us for one final round before the journey home; and an atmospheric and curious beauty it is too, playing with the ringing, overtonal qualities of the music box in its melodies, like countrywoman Colleen, aka Cécile Schott. It comes in from out of the storm and into a pirouette of piano and ondes Martenot, lush and chiming, something of a luxurious Art Nouveaux drawing room about its depths – delicious, eerie also, especially those grave closing chimes.

Without a doubt one of the most potent voices in modern composition today, Christine Ott is as happy to push right out into dark, even industrial-infused experimenta as she is to play a straight bat with absolute confidence in the deeper classical tradition and the wider avant-garde palette; she can do it all, if she chooses, and when she breathes the ondes Martenot into life; there really is no one to touch her.

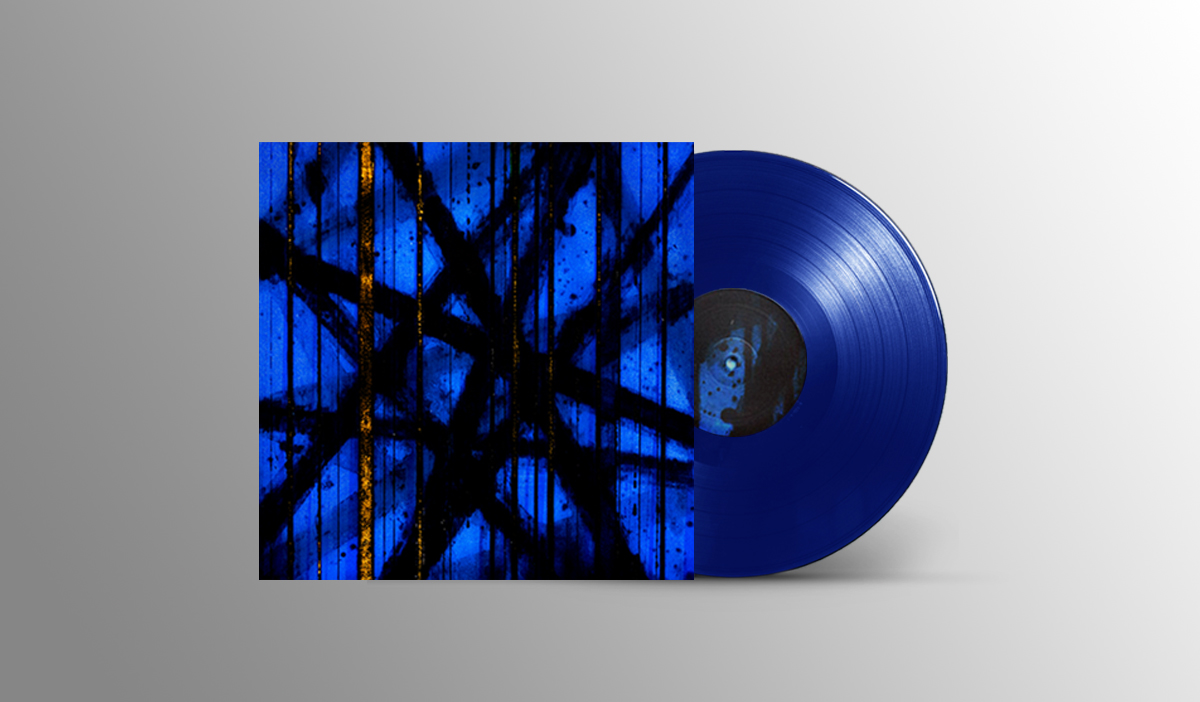

Christine Ott’s Time To Die will be released by Gizeh Records digitally, on CD and on very limited blue vinyl on April 9th; you may pre-order yours direct from the label, here.

No Comment