IF YOU were lucky, then lockdown treated you well; you used the time wisely, fashioned new learning and positivity from the time presented to you.

I had a friend who absolutely flowered during those restrictive weeks; turned her back garden into a vegetable plot, learnt how to paint. It’s fair to say she adored it.

Falkirk folk guitarist Adam Stafford has also come out of that surreal purdah armed with new creative fire.

Spending more time in our domestic environment and giving it a brush and polish, as it seems we pretty much all did – how many crates of free books did you spot out on the verges, seeking new homes? – he discovered a little red notebook hidden beneath some Tupperware in a cardboard box.

It was a forgotten notebook of resonant phrases, part-finished lyrics, ideas spurned at the time; a snapshot of a past life, another Adam. He decided to use his time behind the threshold to reassess what he had to hand; that which he’s partially abandoned to the dust of storage.

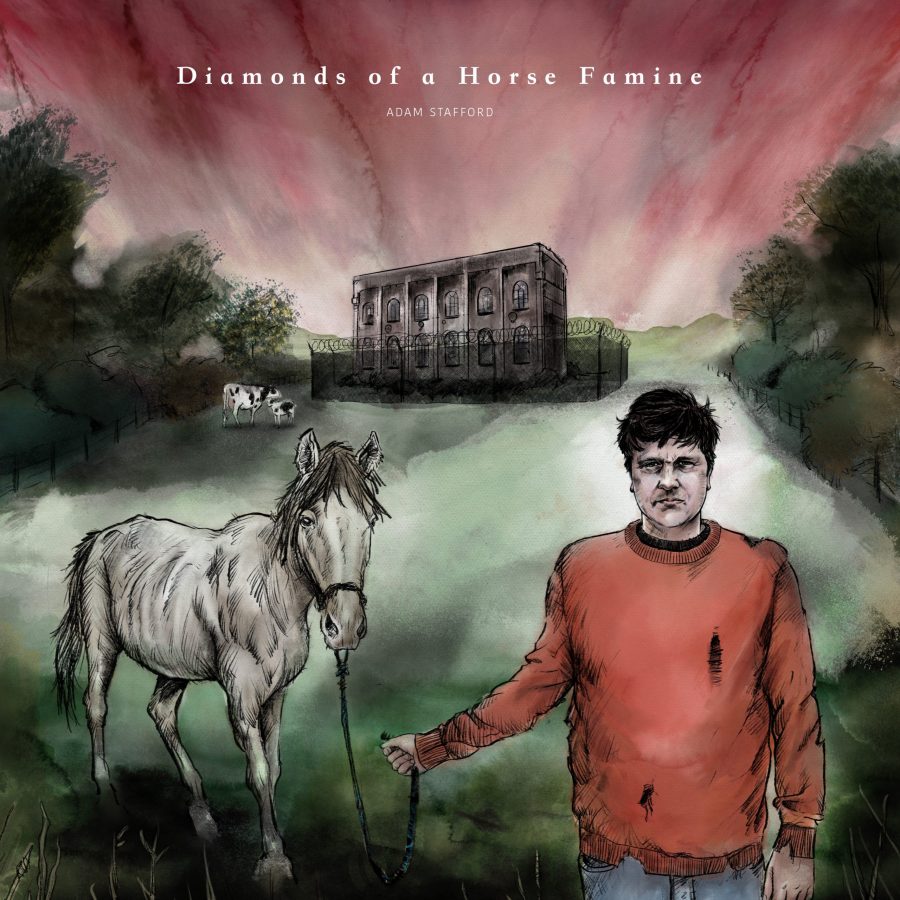

He blew the rime of time from another box, this time that containing his demo tapes; relearned songs laid down and shelved, work up yet others . “I decided to revisit and refurbish them, like a detective looking over an old case,” he says – and thus was his new album, the rather excellent (and excellently named) Diamonds Of A Horse Famine born.

It’s a more vocally-led album than some of his work of late, a conscious decision, he recounts: “People complained that I’d stopped singing when they came to see me live, so this was an opportunity to flex the vocal muscles again and say, ‘Hiya, remember when I used to write lyrics and songs?’.

“I recorded piecemeal for two hours each morning and did vocal takes in my shed at night.”

We begin in “Thirty Years of Bad Road”: a prelude of unobtrusive organ fanfares a crisply plucked acoustic riff – folk in a Roger McGuinn sense, ringing, strong. It’s joined again by a tremulous and cyclical keyboard that runs like a stream behind Adam’s intimately delivered lyricism, which concerns addiction and its handmaiden, inertia. “Waking up with the feeling / That you’ve been walking behind yourself / Looking up at the ceiling / Hungover showers and your bad health”. No Gallagheresque lexical platitudes here. Adam is a very fine lyricist, and there really aren’t too many who are as comfortable with the mechanics and poetics of song.

“History of Longest Days” – now there’s a lockdown kinda nomenclature – sees the warmth of Adam’s voice given free ‘n’ easy vent over warm fingerpicking, lofi and evidently direct from the demo-tape source. There’s little yaws and bends in the sound, the imperfections and chewings of chromium oxide a happy accident. The perfection of a song often lies in such wise imperfections. The longest days of the title are memories of being skint, yet happy in the small things.

“Erotic Thistle”, a single drop a month or so back, is one of the most effortless, graceful yet lyrically idiosyncratic folk songs you’ll hear this side of … well, a direct comparison escapes me. A chiming guitar is bright, even playful; bells pick out the high delightful shimmer of the melody. And the lyrics: stream of consciousness, diaristic, you’ll hear prize lines such as “the tinnitus in my ears sounds like aliens landing,” and yes, “melt down my death mask to fashion it into a dildo” – this last apparently drawn from one of those strange-but-true, weird-world newspaper articles, in which a woman wanted to steal Lenin’s death mask and turn it into an object of self-titillation. The truth is always stranger than fiction. We’ve embedded the lovely video below. Fail to be enamoured.

“That story appealed to my very odd sense of humour,” he says. It also happens to be an almost indecently free-thinking and seductive song. It’s a highlight of Diamonds Of The Horse Famine and definitely vying for the crown for great, erudite, lyrically quirky songs of the past 30 years alongside “Take The Skinheads Bowling”.

The next pair of songs are darker: for “What Kind Of Man” and “Slave”, Adam’s miked up right next to you; the former, on which his voice strains and cracks in service to a sorry tale of an aging woman, her sex appeal ravaged: “What kind of man’s gonna want me / With a body, like a mutilated tree?” Even the desperation of going out hunting a one-nighter results in rejection.

“Slave” burrows into even chillier life experiences: the controlling relationship, the pimped: “Well, you’ll hang yourself for him … He’ll sell your bones for spoons of gilded crystal”. A harp flutters like an anxious heart. The song concludes in a stern and shadowy guitar figure, a smattering of overdrive and a whole bath full of reverb lending atmosphere. There’s a direct line here, for me, right back to the folksong reportage of Ewan MacColl’s seminal Radio Ballads.

The lives lived sadly of these tracks is followed by a brace of blues: the self-confessed tribute to Skip James’ “Little Cow And Calf Is Gonna Die Blues” of 1931, “Calf And Cow Blues”, which paints a vivid picture of a disquieted rural setting; cows crying across the fields waiting to be milked; they’re gonna die real soon, you’ll hear their slaughtered cries.

The title track, “Diamonds Of A Horse Famine”, pitches you into an tossing and turning dream state of part-remembrance. It springs into being on a sustained strum and an eerie voice sample taken from a sermon by an eight-year-old preacher, hitting a slow stride of evocative slide, steeped in a world of white clapboard churches and cotton fields; a Stirlingshire soundtrack to a southern gothic novel.

“I was obsessed with slide blues and Blind Willie Johnson then and this was a kind of tribute,” Adam explains. It was written when he was 19; it’s the oldest track on the album, and pitches you into a complex set of flickering, found imagery, akin to an Adam Curtis film.

“House Is A Hospice” shimmers away on beautifully melodic open playing; Adam sounds confessional, singing just for you. It has lambency and flowing complexity of fellow countryman John Martyn at his best. “I was never taught how to read / It made it harder to spell my name … we conspired against the injustice of our time …”. The lyrical imagery movies quickly, concisely, is so potent.

The concluding track of the nine is “Summer On Elm Wood” – that ‘On’ the clincher, le mot juste; we’re invited to view events from above, in camera. Our subject matter is a child out on the far, blackest edge of depression, writing his (last?) letter under his “Iron Maiden” poster; Adam’s voice and the high lead riff are tremulous, plaintive, seeming to shriek the sick heat of an alienated, disturbed July. The riff builds and powers, builds and powers; it breaks to a lofi shimmer, guitars rattling; the riff returns, stumbling to a (dead?) halt. Silence; resolution.

At about the 34-minute mark, Diamonds Of A Horse Famine is a relatively short album; but don’t make the mistake of conflating that with it being a slight album. There’s a wealth of tales, approaches, styles, herein. Trippy instrumental blues, gliding free association, salutary documentary.

Is it a nostalgia trip of sorts, then? I would argue, no: Adam is in possession of far too much perspicuity to fall for that. He my draw from the past, revisit, but he knows it’s a very different country. Introspection, self-assessment, reassessment, sure. And there’s a noble artistic endeavour at play, too: “It was an attempt,” Adam says, “to strip all of the artifice and return to just voice and minimal instrumentation a la Nick Drake’s Pink Moon, Sparklehorse’s Vivadixiesubmarinetransmissionplot, Cody Chesnutt’s The Headphone Masterpiece and Ry Cooder’s Paris, Texas soundtrack.”

Now that’s a noble intention, executed beautifully.

Adam’s Diamonds of a Horse Famine will be released by Song, By Toad Records on digital and limited red vinyl formats on October 30th. You can place an order for it right now, over here.

No Comment